Thomas Pluck’s website tells us he’s slung hash, worked on the docks, and even swept the Guggenheim museum (but not as part of a clever heist). He hails from Nutley, New Jersey, we’re advised, home to criminal masterminds Martha Stewart and Richard Blake, but has so far evaded capture. He’s a serious student of the martial arts, and a glance at his photo makes it clear he spends a lot of hours at the gym, raising and lowering heavy objects. When he’s not at the gym he’s apt to be on Twitter, sharing barbed comments and cat pictures

Thomas Pluck’s website tells us he’s slung hash, worked on the docks, and even swept the Guggenheim museum (but not as part of a clever heist). He hails from Nutley, New Jersey, we’re advised, home to criminal masterminds Martha Stewart and Richard Blake, but has so far evaded capture. He’s a serious student of the martial arts, and a glance at his photo makes it clear he spends a lot of hours at the gym, raising and lowering heavy objects. When he’s not at the gym he’s apt to be on Twitter, sharing barbed comments and cat pictures

And damned if he doesn’t find time to write, and to good purpose. His work includes the Anthony-nominated crime thriller Bad Boy Boogie and the action-adventure novel Blade of Dishonor, and over fifty published short stories, 21 of which are collected in Life During Wartime.

Tommy contributed to two earlier anthologies of mine, Dark City Lights and Alive in Shape and Color. It’s my pleasure to have him back with a story for At Home in the Dark, and to offer you an early taste of it…

THE CUCUZZA CURSE by Thomas Pluck

The flames danced in Vito Ferro’s rheumy eyes as the intense heat blistered the skin black. The brick beehive of the Neapolitan pizza oven at full fire was as hot as a crematorium, and cooked a pie to perfection in under seven minutes. This gave the crust a crispness on the teeth but left chew in the dough, and melted the sliced rounds of bone-white mozzarella without boiling the bright acidity out of the tomato sauce, like a steel oven would.

The flames danced in Vito Ferro’s rheumy eyes as the intense heat blistered the skin black. The brick beehive of the Neapolitan pizza oven at full fire was as hot as a crematorium, and cooked a pie to perfection in under seven minutes. This gave the crust a crispness on the teeth but left chew in the dough, and melted the sliced rounds of bone-white mozzarella without boiling the bright acidity out of the tomato sauce, like a steel oven would.

“Looks about done, right Uncle Veet?” His grandnephew Peter worked runnels into his soft knuckles with his thumbs, kneading invisible worry beads.

Peter was smart, a college boy—unlike Vito’s stronzo sons—but he chattered when outside of his element.

Vito snapped callused fingers, and Peter slid the wooden paddle, the pizza peel, beneath the pie and brought it to the work counter, where he cut it into uneven eighths with jerky, hesitant thrusts of the roller.

Vito studied the pie solemnly.

His family proudly called themselves Catholics, but their true religion was food. Pizza, in particular. Vito had made a covenant with the god of the oven paid for in toil. In the oven he had built with his own hands, a transfiguration occurred, turning a little flour and water topped with tomato sauce and cheese into a meal that made customers line down the block for hours, and his family lived like barons had in the old country.

Vito slapped Peter on the shoulder. “Bene. Mangia.”

The kid pulled off a slice and bit into it with pride. “It’s good!”

Vito remembered when he’d made his first pie back in Napoli, and felt a little twinge in his chest. He took a slice and noted the droop of the the triangle. The center was the hardest to get right. Too often they were soft and watery. He closed his eyes and chewed slow.

The burning began as a small pill of pain at the back of his throat, then blossomed into fiery agony, as if he’d eaten a spoonful of hot coals from the oven. He ran for the galvanized sink and drank from the faucet like a dog to quench the grease fire in his mouth. Sweat ran down his face and he collapsed to the floor.

#

He woke to Peter fanning him with an apron. When he could talk without agony, he dialed the phone. Hoping he would get no answer. Vito didn’t know what frightened him more—the curse or Aldo Quattrocchi, the mafiosi who’d lent him thirty thousand dollars to open the restaurant, even though he was of an age where he shouldn’t buy green bananas.

He woke to Peter fanning him with an apron. When he could talk without agony, he dialed the phone. Hoping he would get no answer. Vito didn’t know what frightened him more—the curse or Aldo Quattrocchi, the mafiosi who’d lent him thirty thousand dollars to open the restaurant, even though he was of an age where he shouldn’t buy green bananas.

“Calm down,” The voice chilled his ear like he’d opened the deep freeze. “I’ll send the Gagootza.”

#

Stately, tanned Joey Cucuzza, resplendent in a tailored slate suit, pink shirt with its collar open to frame a red Italian horn pendant shaped like a dog dick, listened while the ancient pizza-man beseeched him.

Vito scratched his sunken, gray-haired chest through a sweat-soaked white undershirt.

“You burnt your tongue on a slice of pizza?” Joey fixed things for Aldo Quattrocchi, a captain in the broken family of northern Jersey crime. He had come directly from his no-work job at Port Newark, where he read the newspapers and day-traded when he wasn’t at the gym, out to lunch with the dock boss, or enjoying a nooner in the apartment he kept in Ironbound.

Or visiting Aldo’s Newark subjects, who expected protection for their payments of street tax.

“I explain.” Vito took a grayed rag from the pocket of his chinos and mopped his face.

Vito Ferro was a northern New Jersey institution, the first to make Neapolitan style pies, and had paid street tax on his first shop in Hoboken long before Joey and Aldo were born. Aldo could be sentimental when he wasn’t telling you to tack someone’s fingertips to a table with finishing nails.

He wouldn’t send Joey for that kind of job. They had apes for that. Joey was here because he knew people, and he knew people. Now touching forty, he had come up as a runner for an uncle who ran gay bars for the Jewish mob in Manhattan. He had a reputation as a reasonable if foppish good earner with an even temper, respected by men of violence and friendly enough to be a face with the citizens.

“Got any coffee?” Joey nodded toward the shiny pipeworks of the espresso machine.

“It’s not hooked up yet.” The nephew swallowed spit. College boy had locks of brown curls like a Greek shepherd, no ring, and a nice physique. Eyebrows tweezed, with intelligent eyes above a slack jaw. Hands too soft for labor.

Joey wondered how the kid wound up here.

“How exactly are you spending Mister Quattrocchi’s money?” They’d had the thirty grand for six weeks. You paid your first month on receipt, but they would be late for the next unless business picked up soon.

“I had the oven brought brick by brick from Napoli,” Peter said. “It’s the same one Uncle Veet used in his first pizzeria. It took me a week to find the place. They don’t speak the Italian I learned in school.”

“I had the oven brought brick by brick from Napoli,” Peter said. “It’s the same one Uncle Veet used in his first pizzeria. It took me a week to find the place. They don’t speak the Italian I learned in school.”

Vito winced and sipped milk like he was nursing an ulcer.

Joey had visited Napoli to broker a deal with the Camorra for containers half-filled with fake Gucci handbags and half with young Slovenian women, and the mangled street Italian he’d learned growing up served him well. He’d also picked up a snobbery for classic Neapolitan pizza, and after Vito retired, no one else came close. His sons were clowns in comparison.

“They put up a wall around the oven, turned the place into some Irish pub.”

“My sons, they do this,” Vito sneered. “I retire, give them my business, and they do this to me. Disgraciata!” He drew into himself with shame, then curled back two fingers of his right hand and spat between the horns of pointer and pinky finger. “It is the mal occhio.”

The evil eye.

Joey touched the cornuto, the Italian horn at his throat.

His family was only three generations from the old country, where people were still killed over such things.

“I tell Aldo that, and he’s gonna say ‘Old Vito is pazzo,’ and you know what they do to mad dogs, Mister Vito.”

Vito spread the dollop of saliva into the black and white tiles with the sole of his black loafer. “I bite into the pizza from that oven, it burns me. Tell him, Pietro.”

Peter shrugged helplessly. “He looked like he was dying, Mister Cucuzza.”

Joey buffed manicured nails on his slacks. “Why don’t you make me a pie while you tell me the history of the world part one.”

Vito took a risen ball of dough from a tray in the refrigerator. The short old man was bent and his skin was crepe paper, but his forearms flexed as he tossed the dough. He made quick work of it, then sat to tell the story in the seven minutes of baking.

He wrung his apron in his hands. Embarrassed and afraid, sure of his fate.

Joey listened to the story, even though he’d read it in the newspaper. One son had sued the other over use of the name Original Vito’s Neapolitan Pizza. A reality show was pitched. It became a joke. Vito had enough, coming out of retirement to save his good name.

Except he didn’t have any money.

Except he didn’t have any money.

Like many who came over, Vito had no papers, never applied for a social security number. Everything legit was in his wife’s name, and when she succumbed to cancer, it went to their sons, Sal and Nunzio. When he retired, his boys took everything but the house he lived in, left him squeaking by on his wife’s social security check. No more new Cadillacs every year for Vito.

“Scumbari,” the old man said.

So he went to Aldo, who like most guys his age from Hoboken, loved Frank Sinatra, Fiore’s mozzarella, and Vito Ferro’s Neapolitan pizza.

Vito slid out the pie and cut it with quick swipes of the roller.

Joey folded a slice and took a bite. No fires of hell. Only fresh marinara, the tart milky taste of Fiore’s handmade mozzarella cheese, and Vito’s perfect crust. He grunted in appreciation.

“Have one, Mister Vito.”

Vito looked at the pie as if it were a rattlesnake coiled on the wooden pizza peel. “No, Giuseppe. I have the mal occhio on me. And it comes from my own sons.” He gripped his chest to remove the invisible knife from his heart.

Protection was protection. “We’ll help you, Mister Vito.”

#

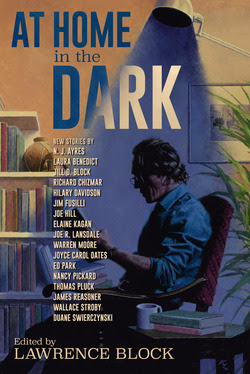

THE CUCUZZA CURSE by Thomas Pluck is one of 17 solid stories in At Home in the Dark. NB: Ebook and paperback editions are on sale now for immediate delivery. DON’T try to order the hardcover, as it’s sold out at the publisher, and while Amazon is still taking orders they’ll be unable to deliver.