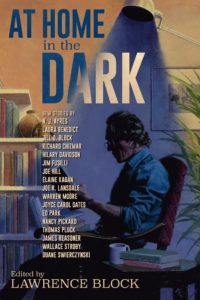

“Duane Swierczynki’s ‘Giant’s Despair’ is a neat bit of Appalachian family drama with drugs, murder and cover-ups at the core, along with a main character who is hampered in his actions by carpal tunnel syndrome gone too long untreated – too real a situation with the current American health insurance climate.” So says Anthony Cardno in his review of At Home in the Dark, while Wes Lukowsky in Booklist has this to say: “Duane Swierczynski’s novella depicts a couple dealing with their adult daughter’s addiction and a criminal son-in-law who wants custody of his daughter. Swiercynski does a masterful job of shifting between past and present to tell his story.”

“Duane Swierczynki’s ‘Giant’s Despair’ is a neat bit of Appalachian family drama with drugs, murder and cover-ups at the core, along with a main character who is hampered in his actions by carpal tunnel syndrome gone too long untreated – too real a situation with the current American health insurance climate.” So says Anthony Cardno in his review of At Home in the Dark, while Wes Lukowsky in Booklist has this to say: “Duane Swierczynski’s novella depicts a couple dealing with their adult daughter’s addiction and a criminal son-in-law who wants custody of his daughter. Swiercynski does a masterful job of shifting between past and present to tell his story.”

With his submission of Giant’s Despair, Swierczy noted that it “runs about 11,000 words. I know 10K was the upper limit, but I’m hoping you won’t mind the extra thousand words, thrown in completely free of charge. I also hope you enjoy it. It’s a dark one, but I think it’s also one of the funniest things I’ve written.”

GIANT’S DESPAIR by Duane Swierczynski

1

Middle of the night is when Lonergan’s hands hurt the most. A lot of his bedtime routine entails fidgeting and turning and trying not to roll over on them. As a result, Lonergan only ever falls partially asleep. He stares at the ceiling, aware of every creak and pop and moan in the house.

So when the frantic knocking comes at 3 a.m. he’s up immediately.

Lonergan glances over at his wife. Jovie, God love her, is still dead to the world, her lips parted a little as she breathes. That is a good thing. They’d had a rough day with the kids. The baby had only gone down a couple of hours ago after much rocking and soothing and lullaby-singing. And the four-year-old continued her giddy mission of destruction throughout the house. It’s like living with a pint-sized terrorist who giggles. That said, the kids are the only things that keep them both going these days.

Lonergan glances over at his wife. Jovie, God love her, is still dead to the world, her lips parted a little as she breathes. That is a good thing. They’d had a rough day with the kids. The baby had only gone down a couple of hours ago after much rocking and soothing and lullaby-singing. And the four-year-old continued her giddy mission of destruction throughout the house. It’s like living with a pint-sized terrorist who giggles. That said, the kids are the only things that keep them both going these days.

A second round of knocks echoes throughout the house, even louder this time.

Lonergan sits up in bed, trying to keep the bedsprings from making too much noise. His hands throb so hard he can feel his heartbeat in them. He’s only wearing skivvies, so he pulls on pajama bottoms and tries to find his slippers in the dark. No luck. Hailee takes a lot of gleeful pleasure in hiding her Pop-Pop’s things. The slippers are probably buried somewhere in the backyard under the snow.

People just don’t turn up at their house. The main road through Bear Creek is Route 115, which rolls along the top of the mountain. To find the Lonergans’ place you have to take a barely-marked gravel road—a glorified driveway actually—and follow up it into the woods. Delivery guys get lost all the time.

Longeran has a feeling who this might be. A cold little hunch in the bottom of his stomach, even as he hopes he’s wrong.

Lonergan hoists himself off the bed and hurries down the hall and into the living room. In the dead silence, each floorboard creek sounds like a scream. He prays the noise won’t wake the baby.

Before he reaches the door, Lonergan considers a run down to the basement. When the kids came to live with them, he made a point of locking up his Smith & Wesson SD9 so his granddaughter would never stumble upon it.

But Lonergan figures by the time he finds the keys, goes downstairs, unlocks the closet, unlocks the safe, unlocks the trigger lock, whoever’s out front will have woken the entire house, maybe even broken down the damn door. So he continues on.

#

Peering through the one-way wide angle viewer, Lonergan sees that he’s guessed right. It’s the son-in-law.

Peering through the one-way wide angle viewer, Lonergan sees that he’s guessed right. It’s the son-in-law.

Son-in-law is wearing shorts, a polo shirt, tennis shoes with no socks. Does he think he’s in the Bahamas instead of upstate Pennsylvania in the middle of February? Granted, it’s been a relatively mild winter up here in the mountains. But that doesn’t mean you should dress to go yachting.

Lonergan hesitates for a minute, hand on the doorknob, steeling himself for whatever bullshit is about to fly out of the boyfriend’s mouth—though he is morbidly curious about what the boyfriend might say after all this time. He flips the lock no problem, but his dumb rubber hands have a hard time grasping the doorknob. By the time he finally manages to open the door with both hands he’s already annoyed.

Son-in-law looks down at Lonergan like he’s anticipating a fight.

“Mr. Lonergan, I want to see my son.”

“Isaiah, it’s three o’clock in the morning.”

“I really need to see him now.”

Lonergan spots a late-model Dodge Charger idling in the driveway, light gray exhaust chugging out of the tailpipe. He didn’t even turn his car off? What, does the son-in-law assume Lonergan will hurry back into the house, dart into the spare bedroom, scoop up the baby and then just hand him over? With maybe some gas money and a hot coffee for the road?

Son-in-law takes Lonergan’s hesitation as an invitation. He steps forward as if to scoot right past him. Lonergan shifts his body to block him.

“Here’s what I need,” Lonergan says. “I need you to turn around and drive the fuck home.”

“You can’t keep me from my son.”

“Maybe not, but I can kick you off my property.”

“I have to see him.”

“Not tonight you don’t.”

Isaiah takes another step forward. Lonergan places a hand on Isaiah’s chest and gives him a firm push back. This should tell him: you’ve gone far enough.

But the son-in-law holds his ground, sensing that maybe he has the advantage. People have underestimated Lonergan since high school—he’s only five seven. And Isaiah is a gangly six four.

“Go home, Isaiah,” Lonergan says. “Before I call the police.”

Lonergan plans on calling the police anyway. As much as Lonergan would like to pound Isaiah Edwards into raw hamburger on the front porch, he knows Isaiah would just hire some fancy lawyer and they’d be in danger of losing the kids.

No, it would be much better if his daughter’s widower turned around, climbed back into his expensive car and drove back to Philadelphia. There’s only one route he can take: I-476, the northeast extension of the turnpike. The state troopers will have plenty of time to pick up Isaiah during his two-hour haul back to the city.

“I don’t have any problems with the police,” Isaiah mutters, but his eyes say the exact opposite.

“I don’t have any problems with the police,” Isaiah mutters, but his eyes say the exact opposite.

“Isaiah, don’t bullshit me at three in the morning. You’ve been on the run for two months. You missed your Daria’s funeral.”

“I couldn’t get back home in time. But I’m here now.”

“Don’t give a shit.”

“Just let me hold him.”

“Not tonight.”

“I was stuck in China on business!”

“Good night,” Lonergan says, then pushes on Isaiah’s chest with his fingertips.

For a moment Isaiah allows himself to be pushed. But then he plants a foot behind him, grabs Lonergan’s hand, and twists.

Fourth of July fireworks blast up Lonergan’s arm and down his spine. He falls to his knees in his own doorway, not even aware that he is screaming. Crushing waves of dizziness wash over him.

But Isaiah doesn’t let go of his hand. He twists, and twists, and twists.

2

The pain started a couple of years ago, and like a typical guy Lonergan ignored it for as long as possible. But at the start of last summer, it got to the point that he couldn’t hold a hammer properly. Diagnosis: carpal tunnel, which meant the thumb and first two fingers of each hand would go numb, tingle, or ache at random intervals.

The doctor whom Lonergan had been seeing as infrequently as possible for the past 20 years said it was simple: he needed surgery. Lonergan told the doc his insurance wouldn’t cover it. The doc looked up his plan and agreed: Lonergan’s insurance wouldn’t cover it. But Lonergan needed surgery nonetheless. They went round and round like this for a while.

Finally the doc agreed to prescribe pain pills, which helped a little. Before, it felt like razor blades were grinding away at the inside of his knuckles. With the pills, it felt like butter knives. The pills did nothing, however, for the bouts of numbness. You need surgery for that, the doctor reminded him. Lonergan reminded the doc that so-called affordable care, in this case, would bankrupt them.

Finally the doc agreed to prescribe pain pills, which helped a little. Before, it felt like razor blades were grinding away at the inside of his knuckles. With the pills, it felt like butter knives. The pills did nothing, however, for the bouts of numbness. You need surgery for that, the doctor reminded him. Lonergan reminded the doc that so-called affordable care, in this case, would bankrupt them.

He tried to work through the pain, but the side effects of those pills included exhaustion, dizziness and nausea. These are not symptoms you want to deal with while building someone a full deck off the back of their house.

So Lonergan’s only option was to take time off work and pray that his hands would heal themselves. Or at least get him back to the point where he could hold his tools. Jovie still had her job at the Woodlands, even though her feet ached all the time, and Lonergan was convinced she was going to need surgery, too. They were the perfect couple. Between the two of them, they had exactly one set of functional appendages.

Had Daria told her boyfriend about Lonergan’s hands? It’s very likely. Lonergan made some of the furniture sitting in their house back in Fishtown. At some point Daria must have told him that her father built those bookcases and that entertainment center with his own two hands, and now he couldn’t work because of those hands. If Isaiah knew, that means he came up here with a plan in mind…

#

GIANT’S DESPAIR by Duane Swierczynski is one of seventeen outstanding works of dark fiction in At Home in the Dark. NB: Ebook and paperback editions are on sale now for immediate delivery. DON’T try to order the hardcover, as it’s sold out at the publisher, and while Amazon is still taking orders they’ll be unable to deliver.

Duane is an extremely talented hard boiled writer. It’s nice to see him getting more exposure.