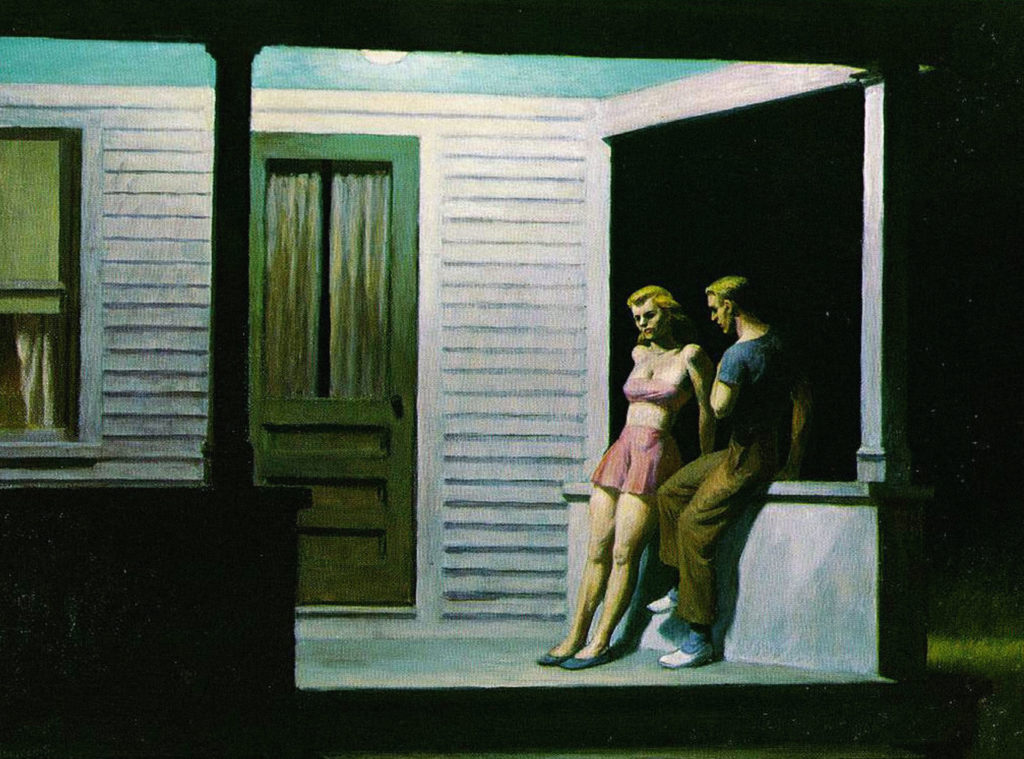

Jill D. Block, who by the sheerest coincidence bears the same surname as the editor of In Sunlight or in Shadow, wrote several promising short stories while in college at Clark University. She went on to a career in corporate real estate law, until an interfering relative suggested there was no need to confine her fiction to legal briefs. Her first story appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, her second in the Three Rooms Press anthology, Dark City Lights. This, her third, was inspired by Edward Hopper’s 1947 painting, “Summer Evening.”

THE STORY OF CAROLINE

By Jill D. Block

HANNAH

Once I decided it was finally time to look, it really wasn’t so hard to find her. After so much anticipation, having prepared myself for the frustrations and disappointments, the false leads, dead ends and wasted money that I assumed were inevitable, it actually took me less than a month. Massachusetts’ open adoption laws helped, and I made some lucky guesses. And then Google and Facebook helped bring it home.

The hard part was figuring out how I was going to get close to her, close enough to look into her eyes, to hear her voice. I wasn’t looking for a big emotional reunion. I certainly didn’t want or expect to forge a relationship at this late date. I didn’t even intend to let her know who I am. This isn’t about her, and I’m not here to answer her questions. I mean, if she was so interested in knowing who I am, she could have looked for me, right?

That sounds like I am mad at her for having given me away. But I’m not. All I really mean is that I don’t assume she has any interest in knowing what became of me. And that’s ok. Look, I’m almost 40 years old. I get it. I learned a long time ago that you can’t blame someone for not loving you.

She was sixteen when she had me. So pretty much wherever I ended up was going to be better than with her, right? And it was fine. The people who raised me, my parents, were perfectly nice, well-meaning people. They were older, in their forties, when they got me, and they took me into their home and made me a part of their family. Well, sort of. Looking back, it seems like once they got me they couldn’t quite remember why they’d bothered. Let’s just say, there was not a lot of love in that house. They raised me, gave me shelter, food and clothes and an education. I know exactly what they did for me, and I appreciate it. Lots of kids grow up with a lot less than I had. But now I need to see what I’d missed.

GRACE

She sat at the kitchen table and listened to him breathing in the next room. She took a sip of coffee. Cold. She should be in there with him. She should be cherishing this time, spending these final days with him, these final moments. She knew that there would come a day, soon, when she wouldn’t remember what kept her paralyzed in here, in this room, when she could have been by his side, and she would be left with nothing but regret.

Missy and Jane had decided when he came home from the hospital that he should be down here, in the family room, and not in the bedroom upstairs. They’d come roaring in like a storm, waving cellphones and Starbucks cups, throwing open the windows, unpacking groceries, rearranging furniture, directing the guys who delivered the bed, acting like they own the place. Like they live here. Like this was their problem to solve. When she brought him home, they sat with him, sometimes together, sometimes taking turns, holding his hand, smoothing his hair, speaking softly to him, kissing his forehead. And then, blinking back their tears, telling her they’d be back soon, they got in their cars and they left.

That was two days ago. Since then, she’d mostly sat here, at the kitchen table, drinking coffee and listening to him breathe. Aside from the feedings every few hours, when she busied herself with detached efficiency, mixing and measuring, chirping and clucking like an idiotic bird, asking him questions she knew he wouldn’t answer, she couldn’t bear to be in the room with him.

The one-sided conversations don’t really bother her. She is used to it. He hasn’t been able to speak for more than two years, not since the last big surgery. He’d tried in the beginning. He would say something, and she would guess, trying to understand what he was saying. She had about as much success as she would have had having a conversation with the cat. They sometimes laughed about it, back when it still felt like they were in this together.

Eventually, they stopped trying. After repeating himself three or four times, and shaking his head no to each of her guesses, he’d dismiss her with a wave of his hand, never mind, and turn back to the newspaper. That was when she felt most like she was failing him. If their bond was really so deep, shouldn’t his words be able to reach her?

If it was important enough, he would write her a note. The house was filled with his notebooks, their spirals crushed, and the pencils he used, sharpened with a knife. What would she do with the notebooks when he was gone? She wondered if the girls would want them. They probably imagined that they would find them full of poetic declarations of love, essays on the singular joy he’d known being their father. In fact, they were mostly reminders of things she needed to pick up at the store. Q-tips and Kitty Litter.

There had been fewer and fewer notes the last few months before he’d gone into the hospital. He responded to her questions with a thumbs up or down, the occasional shrug (which she took to mean “I don’t know” or “I don’t care,” depending on her mood), raised eyebrows (“really?”) or a smile. There hadn’t been many smiles lately.

José had told her he would come everyday, that he would bathe him, and change the bed. He told her he had put a box of medications in the refrigerator, that she could administer as needed, and he stuck a note to the door with a magnet. He left her with a stack of pamphlets, and said that he would arrange for a volunteer to come by every few days.

HANNAH

My plan had been to show up at the gallery where she worked. I figured I would recognize her from her Facebook pictures, and I could just say I was new in town, act confused and ask for directions or something. I would be gone before she noticed if anything I said didn’t make sense…

##

You can read the rest of Jill’s story, and sixteen others, in In Sunlight or in Shadow. In a year or two, if all goes well, you may be able to read the novel on which she’s currently at work. For now, here’s a short video, filmed at the recent ISOIS launch at the Whitney Museum, in which she talks about “The Story of Caroline.”