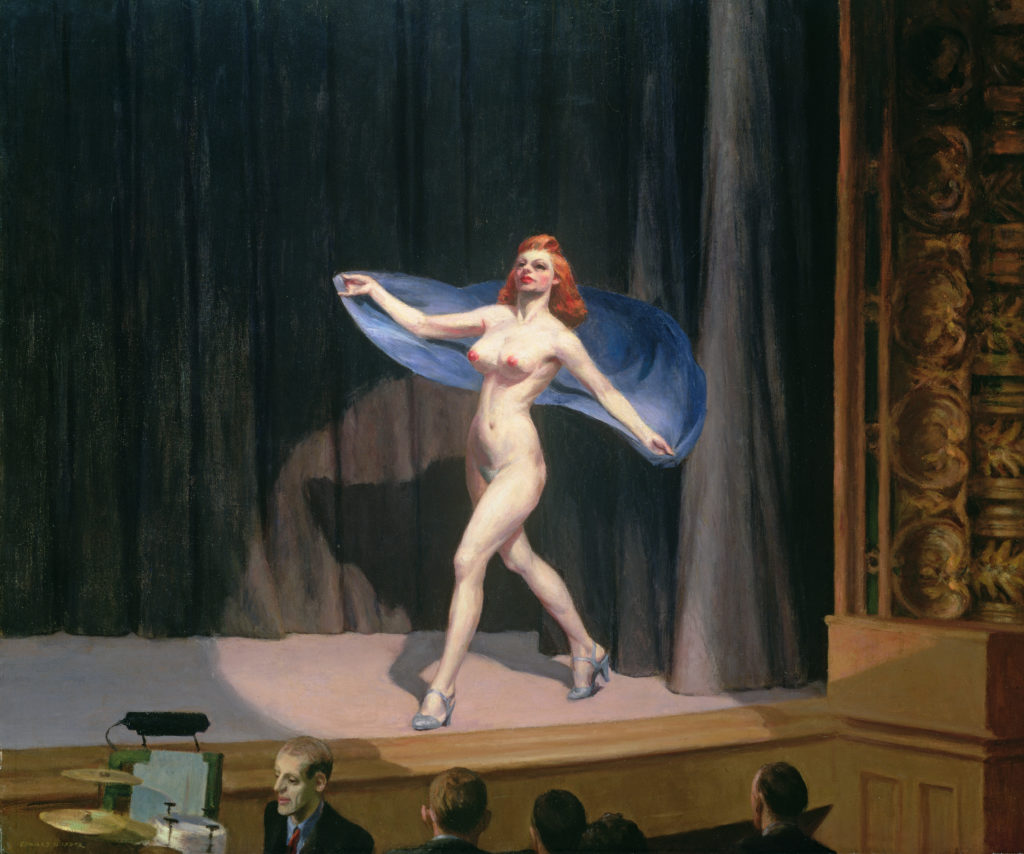

When Jonathan Santlofer learned that Megan Abbott had chosen “Girlie Show” as the inspiration for her story for In Sunlight or in Shadow, he confided that he would have picked it himself if she hadn’t beaten him to it.

“Oh, that would have been a mistake,” she told him. “You’d have gotten in trouble. It’s a story that can only be written by a woman.”

I’d take it a step further. It’s a story that could only be written by Megan Abbott.

Girlie Show

By Megan Abbott

“She went udders out.”

“No pasties even?”

“Like a pair of traffic lights.”

Pauline hears them on the porch. Bud is telling her husband about a trip to New York City a few years ago. Going to the Casino de Paree.

Her husband says almost nothing, smoking cigarette after cigarette and making sure Bud always has a Blatz in hand from the metal cooler beside him.

“Nipples like strawberries,” Bud is saying. “But she never took off her g-string. And she never spread her legs.”

“That right?”

“Maybe you’ve seen things I ain’t.”

“Can’t say I know what you mean,” her husband says, flicking a match onto the lawn.

“Uh-huh.”

After, her husband comes inside, cheeks like dark flames.

The next day, she finds him in the kitchen, working, feet on the table.

It’s the first time he’s taken his sketch pad out in four months. Lately, he’s taken to give Pauline black looks when she came home from work at the ad agency, especially the time she wore the new beaver hat the man from Schmitt’s Fine Furs had given her for all her hard work.

But now, he is sketching frantically, and she doesn’t say a word or stand too close. They’ve been married fourteen years and she knows all his frets and stops, wood warps and sweet spots.

“But it’s so cold,” she says. It’s been so long since he’s asked her she almost thinks it might be some kind of joke.

He needs a model.

“Stand by the stove,” he says, rolling his shirt sleeves above his elbows. That angry vein in his forearm.

She moves over to the cook stove, its frill of heat.

The memory comes back to her, nearly fifteen years before. The coldest January she’d known. Cuddling up to the pot belly stove at the train station, she felt something pressing against her back. Turning, she saw a man behind her, hands deep in his coat pockets, red-cheeked.

She could smell Sen-Sen on his breath and the Macassar oil he used in his hair.

She was startled, but he was so handsome and she was twenty-seven, the only girl from her town without a husband.

They were married three months later.

My masher, she used to call him, affectionately, a very long time ago.

Sketch pad on his knees, he waits as Pauline pulls loose her housedress, unrolls her stockings.

The last is her underdrawers, which shiver to her feet.

“You’ll see all the things I don’t want you to see,” she whispers, throatily. She doesn’t know where this voice comes from.

Wifely duties, married intimacies have never been easy for her. Everything came as a great shock on her wedding night, even though she’d read Ideal Marriage: Physiology and Technique, the book her maid of honor, who’d already been married eighteen months and, as she whispered over creamed coffee at the luncheonette, was now as “looser than a wagon tire” down there.

Pauline hadn’t gotten as far in the book as she should have, or her Latin wasn’t good enough, because it turned out the thing her new husband liked to do most was more than two-hundred pages in, and the movements required, and the sounds he made, she could not find in the book at all.

The parts she liked were the accidental moments, often things she felt almost by accident while he was moving her, hands on her shoulders so rough she had marks like blue petals, and they recalled certain private moments when the subway train braked suddenly, coming to a long, shuddery stop.

Everything is off now, dress, stockings, slip, brassiere, step-ins and she is standing on the kitchen stool. She wonders if a very tall man might be able to see her through the pane above the kitchen curtains.

“Turn to your right.”

She can feel the gooseflesh rise, the veins behind her knees like tickling spiders now.

She is forty-two and no one has asked her to take off her clothes in a long time. (How about lunch, Mr. Schmitt said every time he called now. I’d love to see that beaver on you.)

As she turns, she lifts her breasts, which she’s always been proud of. No puling babies have ever hung from them and they have never fallen like a pair of yeast cakes, as some of the other women she knew confided. Once, Mrs. Bertrand, the head of the switchboard at the office asked if she could touch Pauline’s breasts, just to remind myself.

Catching a glimpse of herself in the chrome toaster, she smiles a little, but only to herself.

He makes her take many different poses, her arms high and twined like Marlene Dietrich, her legs apart, a boxer’s stance. Hand on hip, like a department store model, and knees bent, hands on hips, like a momma saying kootchie koo to a baby in a stroller.

“What is this for?” she finally asks, her back aching, her body tingling head to toe. “Am I dancer or something?”

“You’re not anything,” he says, coolly. “But the painting will be called the ‘Irish Venus.’”

She used to pose for him the first few years they were married, but only for his pay-work. She posed as an aproned housewife (Romance dies at the sight of dishpan hands!), a bathing beauty (Ten more pounds changed my life. A skinny girl hasn’t a chance!), a June bride, a beer hall girl in lederhosen. Eventually, once she started bringing in regular pay at the ad agency, where she drew herself all day (rows and rows of women’s shoes, or men’s hats, or children’s pajamas), he suggested he start hiring girls from the art school, but she resisted.

“Don’t be so jealous,” he would say.

“It’s the only time we spend together,” Pauline insisted, gently.

But then one time, she came home late from work, soon after her promotion.

The canvas on his easel was torn in half and he was gone to McCrory’s till four. When he finally returned, knocking over the milk bottles on the front step, he did some nasty things under their covers that she was required to be part of. She had to go to a doctor the next day and have some stitches put inside. Pushing through the train turnstile made her cry in pain.

He swore he didn’t remember any of it, but the following week, he hired a girl from the art school. She had buck teeth, but he said it worked out because she always kept her mouth shut.

##

Read the rest of Megan’s story—and Jonathan’s, and fifteen more by fifteen outstanding writers—in In Sunlight or in Shadow.