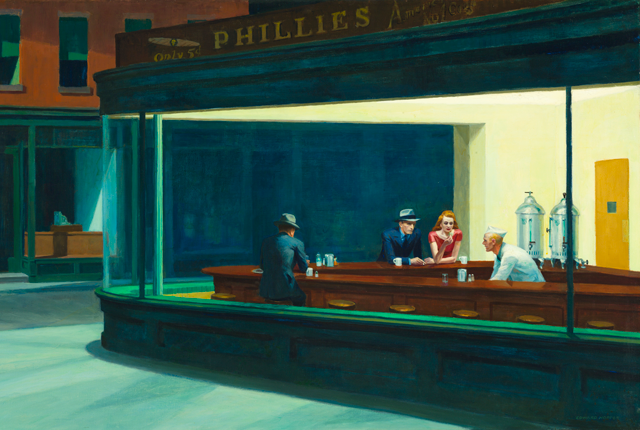

Hieronymus Bosch, the 15th Century Dutch painter, has a namesake in Michael Connelly’s iconic series detective, who’s known to all as Harry. And Harry in turn has had a longstanding connection to Edward Hopper’s most familiar work, Nighthawks. And here, in his story for In Sunlight or in Shadow, Harry comes face to face with the work.

Nighthawks

by Michael Connelly

Bosch didn’t know how people in this place could stand it. It felt like the wind off the lake was freezing his eyeballs in their sockets. He had come totally unprepared for the surveillance. He had layers on but his top layer was an L.A. trench coat with a thin zip-in liner that wouldn’t keep a Siberian husky warm in the Chicago winter. Bosch wasn’t a man who gave much credit to clichés but he found himself thinking: I’m too old for this.

The subject of his surveillance had come down Wabash and turned south on Michigan, moving along Grant Park. Bosch knew where she was going because she had headed this way on her lunch break at the bookstore the day before as well. When she got to the museum she showed her member pass and was quickly admitted entrance. Bosch had to wait in line to buy a day pass. But he wasn’t worried about losing her. He knew where she would be. He didn’t bother to check his coat because he was cold to the bone, and he didn’t expect to be in the museum more than an hour – the girl would have to get back to the bookstore.

He moved through the galleries quickly on a direct route to the permanent Hopper exhibition. There he found her sitting on the one long bench. She had her notebook and pencil out and was already working. He had been surprised the day before to find she was not sketching in her notebook as she repeatedly glanced up and studied the painting. She was writing.

Bosch surmised that the Hopper painting was the biggest draw in the museum. Many people came for it and often carelessly stood in front her, blocking her view. She never cleared her throat to alert them. She never said anything. She sometimes leaned to her left or right to see around one of the blockers and Bosch thought he would see a slight smile on her lips, as though she were pleased with what the new angle of observation had brought her.

The lone bench was crowded with four Japanese tourists sitting in a row next to her. They looked like high school students come to study the master’s most well known work. Bosch took a position on the other side of the gallery, behind the surveillance subject’s back so she wouldn’t notice him. He rubbed his hands together and tried to get some warmth into them. His joints were aching from the cold and the nine-block walk to the museum. He had found no interior space with an angle on the front doors of bookstore. He had waited outside, hovering around the entrance to a garage, for her to emerge at lunchtime.

Bosch saw a spot on the opposite end of the bench come open when one of the students got up. He moved toward it, sitting down and using the three students between him and the surveillance subject as a blind. Without leaning forward and exposing himself he tried to look down the bench and possibly see what she was writing in her notebook. But she was writing with her left hand and that blocked his view.

He looked up at the painting when there was a moment the crowd cleared and it could be seen clearly. His eyes were drawn toward the man sitting alone at the counter, his face turned toward the shadows of the painting. There was a couple sitting across the counter from him. They looked bored. The man sitting alone was ignoring them.

“Iku jikan.”

Bosch turned his eyes from the painting. An older Japanese woman was signaling the sitting students impatiently. It was time to go. The two girls and a boy stood up and scurried out of the gallery to join the rest of their classmates. Their five minutes with the masterpiece were up.

That left Bosch alone on the bench with the subject of his surveillance. Four feet of space on the bench separated them. Bosch realized that sitting down had been a strategic mistake. She could get a good look at him if she looked away from the painting and her notebook. She might remember him if this lasted another day.

He didn’t move at first because that might draw her eye. He decided to wait two minutes and then get up. He would turn quickly away so she wouldn’t see his face. In the meantime, she did not seem to notice his presence and he went back to looking at the painting. He wondered about the painter’s choice to show the interior of the diner from the outside. To paint it from the shadows of night.

But then she spoke.

“Magnificent, isn’t it?” she asked.

“Excuse me?” Bosch asked.

“The painting. It’s pretty magnificent.”

“That’s what they say, yes.”

“Who are you?”

Bosch froze.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“Which one of them do you identify with?” she said. “You’ve got the man by himself, the couple who don’t look all that happy to be there, and the man working behind the counter. Which one are you?”

Bosch turned from her to look at the painting.

“I’m not sure,” he answered. “How about you?”

“Definitely the loner,” she said. “The woman looks bored. She’s checking her nails. I’m never bored. It’s the one all alone.”

Bosch stared at the painting.

“Yeah, me too, I guess,” he said.

“What do you think the story is?” she asked.

“What, with them? What makes you think there’s a story?”

“There’s always a story. Painting is story telling. Do you know why it’s called Nighthawks?”

“No, not really.”

“Well, the night part is obvious. But check out the beak on the guy with the woman.”

Bosch did. He saw it for the first time. The man’s nose was sharp and bent like a bird’s. Nighthawks.

“I see it,” he said.

He smiled and nodded. He had learned something…

# # #

You can read the rest of Michael’s story—and 16 other stories based on Edward Hopper paintings—in In Sunlight or in Shadow.

As always, thanks for that, Michael and Harry.

When is Connelly going to publish a short story collection? He has enough of them.

You’d have to ask Michael. When he does, I’ll be first in line for a copy.