A picture, as you’ve been told all your life, is worth a thousand words. And what better way to give you a taste of In Sunlight or in Shadow than to show you the Edward Hopper paintings that inspired the book’s 17 authors, and to furnish 1000 words of each of their stories?

We’ll lead off today with “Sour Bleu,” by Robert Olen Butler.

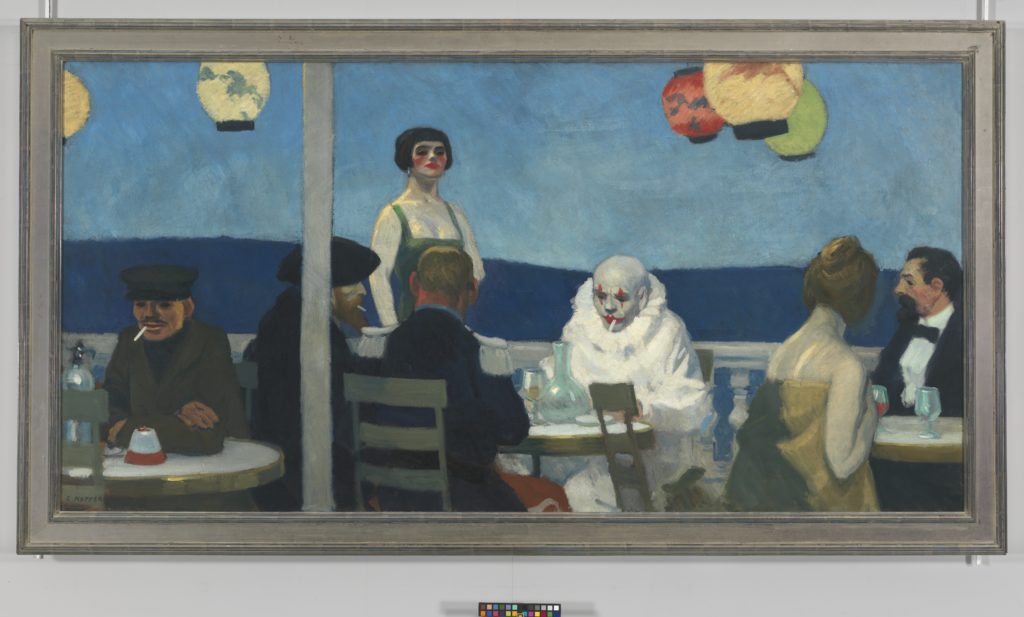

Soir Bleu

by Robert Olen Butler

While I’ve been distracted, the clown has taken a seat at our veranda table in absolute silence. But of course. He is, after all, Pierrot, and beneath the makeup, a mime.

Damnable distraction. Before I knew the clown was there, Colonel Leclerc, sitting at my right hand, was leering at Solange, who returned from a freshening inside the hotel and stopped to vamp for him. I could not bear to see her play at being the woman she once was. I’d rescued that woman from the Place Pigalle and made her my model. I’d redeemed her nakedness with my art. But Leclerc would rather buy her than one of my paintings. Instead of a Vachon, he would have the artist’s erstwhile whore.

All this flared through my limbs, so I forced my eyes to go beyond her, out to the Esterel Mountains and the twilight that has begun to transform the cerulean blue of afternoon into the Prussian blue of incipient night. I thought: This present shade is on my fingertips even now. I have come to Nice to paint, not just to hawk. She is a whore no longer. She is exalted. She is my Muse. My necessary Muse. She knows that.

With this I looked from the Esterels back to Solange. At her toilette she’d painted her cheeks and her mouth afresh. Heavily. Luridly. She’d created a nakedly empassioned face. But she immediately shot me her eyes. I know the nuance of her looks. I have painted them. This look was to say: I will snare him for you. He will buy your paintings. He will have me only through you.

This is what she told me. All of this in the briefest of glances. She returned her attention at once to the colonel, and they continued.

So I lowered my face and looked across the table.

And he was there.

He did not startle me. I had already taken my seat in the theater. I had already begun to watch a scene from the Commedia. Colonel Leclerc and Solange—as Il Capitano and Columbina—were so absorbed in each other they did not even notice Pierrot’s entrance. They still haven’t.

Now we look at each other, Pierrot and I. He is painted as if by a child using Delacroix’s palette, his hairless head and face done in zinc white, his outsized lips and his arched brows and the tears of the cuckold falling from his eyes done in vermilion. This is the living portrait of the tormented clown painted on the canvas of the actor’s face. The theaters are near this hotel, along the Avenue de la Gare. He has, no doubt, come straight from a performance. Perhaps he too is hawking, for his troupe.

His eyes are deep in darkened sockets. But that is the actor, not the clown. Perhaps he is old. Perhaps he just did not have the strength tonight to remove his makeup. Not till he can drink for a time.

Those eyes in shadow are impossible to read.

But we stare at each other for a long moment and then he mimes with two fingers the drawing of a cigarette to his lips and, with a flourish of his other hand, mimes the striking of a match and the lighting up, and then the blowing of a perfect smoke ring, which I fancy I can actually see. He angles his head. I cannot see his eyes well enough but I imagine he has just winked.

I understand.

From my inside pocket I pull my pack of Gitanes, but with a crooked smile Pierrot flips his chin and unfurls his right hand. He has conjured a lit cigarette. He puts it in his mouth and he drags deep and blows a real smoke ring, which dilates toward me.

I look to Leclerc.

He is still enrapt with Solange.

The ring of smoke drifts beneath his gaze and dissolves without his noticing.

I return to Pierrot and we smoke together for a time, long enough to twice mingle plumes above the table. Between the first and the second, Solange sits down to my left. I do not need to look at her or at the colonel to feel their gaze still linked together.

And then Leclerc addresses me. “Monsieur Vachon. I offer my apologies to you and to Mademoiselle. I am weary and will retire. I will come in the morning to choose a painting.”

I turn my face to him.

He is looking past me.

“But of course,” I say.

He rises.

He goes.

I watch his wide, muscled back move away, rendered in Napoleonic blue.

I turn to Solange.

She smiles. “He will buy,” she says.

I cannot help but hear the ambiguity. Still, I overcome this. After all, she has fallen deeply in love with my genius. She has fallen in love with the image of herself I’ve made for her. I have revealed the true colors of her flesh, in sunlight and shadow, in sleep and in passion. Beneath the garish colors she has used to paint the ardent face she presents to Leclerc, only I know the true flush of her cheeks, the raw sienna and yellow ochre and cadmium red of it. We have come to understand, Solange and I, that in the deepest sense she no longer exists except by my hand.

She has been looking only at me since Leclerc left. I glance at Pierrot and he is staring at me as well, unwaveringly, solemn-faced. I look back to Solange and I unfurl my hand in the clown’s direction, as he did in his bit of legerdemain.

She follows the gesture.

She registers nothing. Indifference. Not even this incongruous figure can shake her from her intentions. I think: She has her mind on the tin-pot soldier.

I am tired of this. I do not wish to drink my wine and smoke my cigarettes while trying to read her mind.

“Go up now,” I say to her.

###

That’s it for now, I’m afraid. This picture’s worth quite a bit more than 1000 words, and you can read the rest of them—and another 16 stories, each illustrated with its own magnificent painting—in the new book from Pegasus, In Sunlight or in Shadow.