It’s tempting to regard Joyce Carol Oates as a force of nature. She so consistently produces such an abundance of well wrought and richly imaginative fiction that one might picture her simply turning on a faucet and letting the words flow. But the fact of the matter is that Joyce gets so much accomplished because she devotes so much time and energy to it. It doesn’t hurt, of course, that she’s blessed to an astonishing degree with talent and imagination, but it’s hard work that gets it all on the page, and polishes it until it gleams.

It’s tempting to regard Joyce Carol Oates as a force of nature. She so consistently produces such an abundance of well wrought and richly imaginative fiction that one might picture her simply turning on a faucet and letting the words flow. But the fact of the matter is that Joyce gets so much accomplished because she devotes so much time and energy to it. It doesn’t hurt, of course, that she’s blessed to an astonishing degree with talent and imagination, but it’s hard work that gets it all on the page, and polishes it until it gleams.

I don’t believe there’s anything of Joyce’s I wouldn’t recommend. Among the story collections, the excellent Beautiful Days is on offer right now at a very attractive price. Among the novels, Hazards of Time Travel shows that its author has never stopped growing, or taking chances. And her memoir, A Widow’s Story, is heart-rendingly real and deeply affecting.

THE FLAGELLANT by Joyce Carol Oates

Not guilty he’d pleaded. For it was so. Not guilty in his soul.

Not guilty he’d pleaded. For it was so. Not guilty in his soul.

In fact at the pre-trial hearing he’d stood mute. His (young, inexperienced) lawyer had entered the plea for him in a voice sharp like knives rattling in a drawer—My client pleads not guilty, Your Honor.

Kiss my ass Your Honor— he’d have liked to say.

Later, the plea was changed to guilty. His lawyer explained the deal, he’d shrugged O.K.

Not that he was guilty in his own eyes for he knew what had transpired, as no one else did. But Jesus knew his heart and knew that as a man and a father he’d been shamed.

#

At the crossing-over time when daylight ends and dusk begins they approach their Daddy and dare to touch his arm.

He shudders, the child-fingers are hot coals against bare skin.

Hides his face from their terrible eyes. On their small shoulders angel’s wings have sprouted sickle-shaped and the feathers of these wings are coarse and of the hue of metal.

Holy Saturday is the day of penitence. Self-discipline is the strategy. He’d promised himself. On his knees he begins his discipline: rod, bare skin.

(Can’t see the welts on his back. Awkwardly twists his arm behind his back, tries to feel where the rod has struck. Fingering the shallow wounds. Feeling the blood. Fingers slick with blood.)

(Not so much pain. Numbness. He’s disappointed. It has been like this—almost a year. His tongue has become swollen and numb, his heart is shrunken like a wizened prune. What is left of his soul hangs in filthy strips like a torn towel.)

(Not so much pain. Numbness. He’s disappointed. It has been like this—almost a year. His tongue has become swollen and numb, his heart is shrunken like a wizened prune. What is left of his soul hangs in filthy strips like a torn towel.)

#

Lifer. He has become a lifer.

But lifer does not mean life. He has learned.

#

Shaping the word to himself. Lifer!

—twenty-five years to life. Which meant—(it has been explained to him more than once)—not that he was sentenced to life in prison but rather that, depending upon his record in the prison, he might be paroled after serving just twenty-five years.

Incomprehensible to him as twenty-five hundred years might be. For he could think only in terms of days, weeks. Enough effort to get through a single day, and through a single night.

But it was told to him, good behavior might result in early parole.

Though (it was also told to him) it is not likely that a lifer would be paroled after his first several appeals to the parole board.

Where would he go, anyway? Back home, they know him and he couldn’t bear their knowledge of him, their eyes of disgust and dismay. Anywhere else, no one would know him, he would be lost.

Even his family. His. And hers, scattered through Beechum County.

Who you went to high school with, follows you through your life. You need them, and they need you. Even if you are shamed in their eyes. It is you.

Problem was, remorse.

Problem was, remorse.

Judge’s eyes on him. Courtroom hushed. Waiting.

What the young lawyer tried to explain to him before sentencing–If you show remorse, Earle. If you seem to regret what you have done…

But he had not done anything!—had not made any decision.

She had been the one. Yet, she remained untouched.

#

Weeks in his (freezing, stinking) cell in men’s detention. Segregated unit.

Glancing up nervous as a cat hearing someone approach. Or believed he was hearing someone approach. Thought came to him like heat lightning in the sky—They are coming to let me out. It was a mistake, no one was hurt.

Or, thought came to him that he was in the other prison now. State prison. On Death Row. And when they came for him, it was to inject liquid fire into his veins.

You know that you are shit. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. That’s you.

No one came. No one let him out, and no one came to execute him.

He didn’t lack remorse but he didn’t exude a remorseful air.

A man doesn’t cringe. A man doesn’t get down onto his knees. A man doesn’t crawl.

His statement for the judge he’d written carefully on a sheet of white paper provided him by his lawyer.

I am sorry for my roll in what became of my children Lucas & Ester. I am sorry that I was temted to anger against the woman who is ther

mother for it was this anger she has caused that drove me to that place. I am sorry for that, the woman was ever BORN.

Pissed him that the smart-ass lawyer wanted to correct his spelling. Roll was meant to be role. Ester was meant to be Esther.

The rest of his statement, the lawyer would not accept and refused to pass on to the judge. As if he had the right.

Took back the paper and crumpled it in his hand. Fuck this!

Anything they could do to you, to break you down, humiliate you, they would. Orange jumpsuit like a clown. Leg-shackles like some animal. Sneering at you, so ignorant you don’t know how to spell your own daughter’s name.

Sure, he feels remorse. Wishing to hell he could feel remorse for a whole lot more he’d like to have done when he’d had his freedom. Before he was stopped.

#

Covered in welts. Bleeding.

Covered in welts. Bleeding.

A good feeling. Washed in the blood of the Lamb.

He believes in Jesus not in God. Doesn’t give a damn for God.

Pretty sure God doesn’t give a damn for him.

When he thinks of God it’s the old statue in front of the courthouse. Blind eyes in the frowning face, uplifted sword, mounted on a horse above the walkway. Had to laugh, the General had white bird crap all over him, hat, shoulders. Even the sword.

Why is bird crap white?—he’d asked the wise-ass lawyer who’d stared at him.

Just is. Some things just are.

But when he thinks of Jesus he thinks of a man like himself.

Accusations made against him. Enemies rising against him.

Welts, wounds. Slick swaths of blood.

Striking his back with the rod. Awkward but he can manage. Out of contraband metal, his rod.

It is (maybe) not a “rod” to look at. Your eye seeing what it is would not see “rod.”

Yet, pain is inflicted. Such pain, his face contorts in (silent) anguish, agony.

As in the woman’s sinewy-snaky body, in the grip of the woman’s powerful arms, legs, thighs he’d suffered death, how many times.

Like drowning. Unable to lift his head, lift his mouth out of the black muck to breathe. Sucking him into her. Like sand collapsing, sinking beneath his feet into a water hole and dark water rising to drown him.

The woman’s fault from the start when he’d first seen her. Not knowing who she was. Insolent eyes, curve of the body, like a Venus fly trap and him the helpless fly: trapped.

#

Plenty of time in his cell to think and to reconsider. Mistakes he’d made, following the woman who’d been with another man the night he saw her. And her looking at him, allowing him to look at her.

Sex she baited him with. The bait was sex. He hadn’t known (then). He has (since) learned.

Sex she baited him with. The bait was sex. He hadn’t known (then). He has (since) learned.

He’d thought the sex-power was his. Resided in him. Not in the woman but in him as in the past with younger girls, high-school-age girls but with her, he’d been mistaken.

And paying for that mistake ever since.

To be looked at with such disgust. To be sneered-at. That was a punishment in itself but not the kind of punishment that cleansed.

In segregation at the state prison as he’d been at county detention because he’d been designated a special category of inmate because children were involved and this would be known. Because there was no way to keep the charges against him not-known. Because once you are arrested, your life is not your own.

Surrounded by “segregated” inmates like himself. Not all of them white but yes, mostly white.

Yet nothing like himself….

#

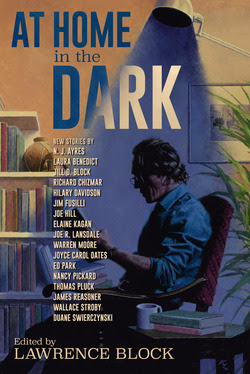

THE FLAGELLANT by Joyce Carol Oates is one of 17 remarkable new stories in At Home in the Dark. NB: Ebook and paperback editions are on sale now for immediate delivery. DON’T try to order the hardcover, as it’s sold out at the publisher, and while Amazon is still taking orders they’ll be unable to deliver.