Jill Emerson’s in the spotlight this week, with Neda Ulaby’s mention on NPR’s Morning Edition:

Jill Emerson’s in the spotlight this week, with Neda Ulaby’s mention on NPR’s Morning Edition:

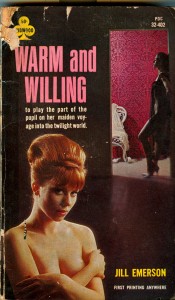

“Before Scudder, Block wrote lesbian erotica under the name Jill Emerson. While they may have been sensitive, they also had titles like Warm and Willing and belonged in the category of pulp fiction known for covers of women in lingerie silhouetted against bedrooms doors. For a while, Block disavowed those novels, but these days he’s proud of them. He remembers having an off-mic conversation with Fresh Air’s Terry Gross a few years ago in which she said, “But Larry, you’re not actually a lesbian.” His reply: “That’s only an accident of birth.”

There have been eight books with Jill Emerson’s name on them, seven back in the day and the eighth just two years ago. All are eVailable. The seven Open Road titles are free to Kindle Unlimited subscribers—and reasonably priced to everyone else, for Kindle, Nook, Kobo, and Apple. The new one, Getting Off, while not a KU title, is readily available as a hardcover, paperback, or ebook.

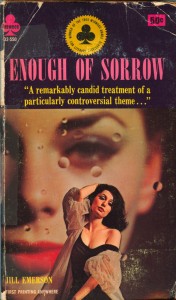

Jill’s work varies greatly from book to book, so let’s take them in turn. Her first two titles, Warm and Willing and Enough of Sorrow, are sensitive novels of the lesbian experience, both published by Midwood as paperback originals. (Enough of Sorrow was my title, drawn from a short poem by Mary Carolyn Davies. Warm and Willing was Midwood’s title, and I’ve always regretted it.)

Jill’s work varies greatly from book to book, so let’s take them in turn. Her first two titles, Warm and Willing and Enough of Sorrow, are sensitive novels of the lesbian experience, both published by Midwood as paperback originals. (Enough of Sorrow was my title, drawn from a short poem by Mary Carolyn Davies. Warm and Willing was Midwood’s title, and I’ve always regretted it.)

In 1964, after having published perhaps fifty books, a dozen of them with Midwood, I parted company with my agent—which closed several markets to me. While Midwood wasn’t a closed shop, something led me to write W&W—I forget what I’d called it—and send it in over the transom, with a cover letter signed by Jill Emerson. The editor, one John Plunkett, bought it by return mail, and was similarly receptive a few months later to Enough of Sorrow. Someday I’ll dig out my correspondence with Mr. Plunkett and share the letters with y’all. He got a tad flirty with Jill, talking about the good time he had auditioning cover models. Jill replied that she “really liked the little darling with the long-drink look.”

Well, that’s our girl for you.

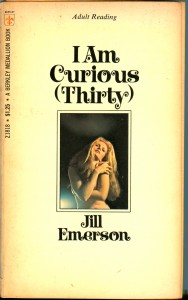

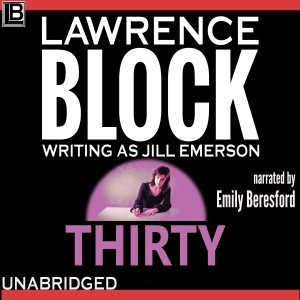

Jill turned up next in 1970. Berkley was responding to the New Freedom by starting up a line of erotic fiction with some literary value, and it looked like an opportunity for Jill. At the time, I was going through a stretch where the novel as such seemed unacceptably artificial to me. Whose voice was recounting it to us? And how did it all get on the page, anyway? I felt more comfortable with the notion of a book that pretended to be an actual document of some sort. I’d also come to realize that a thirtieth birthday was a watershed moment in a woman’s life, and so my first book for Berkley was Thirty, a diary begun on the narrator’s twenty-ninth birthday and chronicling the ensuing twelve months.

Jill turned up next in 1970. Berkley was responding to the New Freedom by starting up a line of erotic fiction with some literary value, and it looked like an opportunity for Jill. At the time, I was going through a stretch where the novel as such seemed unacceptably artificial to me. Whose voice was recounting it to us? And how did it all get on the page, anyway? I felt more comfortable with the notion of a book that pretended to be an actual document of some sort. I’d also come to realize that a thirtieth birthday was a watershed moment in a woman’s life, and so my first book for Berkley was Thirty, a diary begun on the narrator’s twenty-ninth birthday and chronicling the ensuing twelve months.

Some wet-brained doofus at Berkley retitled the book I Am Curious—Thirty, in order to cash in on the cachet of I Am Curious—Yellow, a tedious bit of Swedish cinematic erotica that had its fifteen minutes of fame when Jackie  Kennedy, caught leaving the theater by a papparazzo, displayed some unexpected martial arts skills and knocked the pest on his ass. I hated this title a whole lot more than I hated Warm and Willing, and made sure to change it for the Open Road ebook. (And it’s Thirty on the new audiobook, narrated by the incomparable Emily Beresford and to be released any day now.)

Kennedy, caught leaving the theater by a papparazzo, displayed some unexpected martial arts skills and knocked the pest on his ass. I hated this title a whole lot more than I hated Warm and Willing, and made sure to change it for the Open Road ebook. (And it’s Thirty on the new audiobook, narrated by the incomparable Emily Beresford and to be released any day now.)

Next up was a book that’s a personal favorite of mine. (I have, I blush to admit, more than a couple of personal favorites. Well, if I don’t love these books, how can I expect you to?) Again, I wanted to write a book that wasn’t a novel in the traditional sense, and drew inspiration from a highly successful (if not very good) collaborative novel produced by a batch of reporters and feature writers at Long Island Newsday. They called it Naked Came the Stranger, promoted it cleverly, and sold a lot of books.

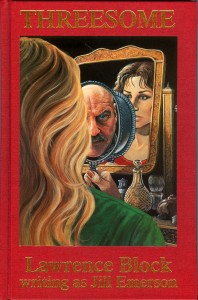

So I wrote a book with three narrators, two women and a man, participants in a menage a trois, who are themselves inspired by Naked Came the Stranger to take turns writing chapters in order to tell their own story. But of course their story evolves as they tell it, and, well, it was enormous fun to write, and very much a tour de force—a French phrase I’m pleased to use, if only to keep menage a trois company.

So I wrote a book with three narrators, two women and a man, participants in a menage a trois, who are themselves inspired by Naked Came the Stranger to take turns writing chapters in order to tell their own story. But of course their story evolves as they tell it, and, well, it was enormous fun to write, and very much a tour de force—a French phrase I’m pleased to use, if only to keep menage a trois company.

I called it Three. Berkley changed the title to Threesome, and I found that acceptable. And (he said grudgingly) probably an improvement.

Robin McLaughlin gave Threesome a lengthy and lovely five-star review at Amazon, and I can’t refrain from quoting a paragraph:

“I count twenty-five passages that I underlined on my Kindle while reading. Some because they were laugh-out-loud funny, some because of clever wording, and some because they were insightful. Yes, I said insightful, and I meant it. It feels really odd (embarrassing?) to admit that one of my most highlighted books on my Kindle is an erotic pulp novel, but there you are. The funny is what surprised me the most. Threesome is downright hilarious, not because of the subject matter, but because of how witty Block is. His writing style is wonderful.”

I’d show you the original Berkley cover, but I don’t seem to have a scan of it. The book’s genuinely rare, and commands a three-figure price when it does turn up. The cover shown is from the 1999 hardcover limited edition published by A.S.A.P. in tandem with Subterranean Press.

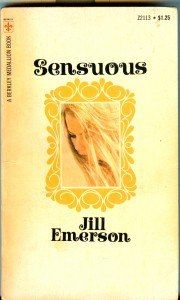

Next up is A Madwoman’s Diary, and it’s the diary form revisited, the title an homage to Sue Kaufman’s Diary of a Mad Housewife. (And, as Donald Westlake has helpfully pointed out, homage is the French word for plagiarism.) It hardly mattered, as Berkley, ever inventive, retitled the book Sensuous—in order to echo The Sensuous Woman, a nonfiction bestseller of the day.

Next up is A Madwoman’s Diary, and it’s the diary form revisited, the title an homage to Sue Kaufman’s Diary of a Mad Housewife. (And, as Donald Westlake has helpfully pointed out, homage is the French word for plagiarism.) It hardly mattered, as Berkley, ever inventive, retitled the book Sensuous—in order to echo The Sensuous Woman, a nonfiction bestseller of the day.

A Madwoman’s Diary, I should point out, has at its very heart an act of flagrant self-plagiarism—or, if you prefer, auto-homage. In one of my John Warren Wells books, I fabricated a case history that somehow stayed with me, so much so that I decided to make a novel out of it. IIRC, Jill paid that debt by dedicating the book to John Warren Wells. It was, she felt, the very least she could do.

Next came an epistolary novel, the letters to and from Laurence Clarke, the ingenious if unprincipled protagonist. Enough early readers enthused over the book to prompt my agent to offer it for hardcover publication under my own name, and Bernard Geis brought it out as Ronald Rabbit is a Dirty Old Man. So it’s not one of Jill’s books, but it started out that way.

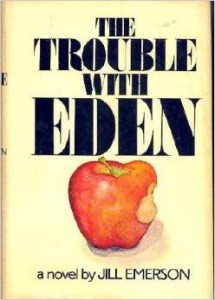

Jill’s next book, The Trouble With Eden, was supposed to be a hardcover bestseller. That was Berkley’s idea; they asked for a big Peyton Place kind of novel, and I wrote one set in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where I’d had the bad judgment to open an art gallery, and the good sense a year later to close it. It got a very strange review in Esquire, where the reviewer said he thought when he started it that it was really quite good, but changed his mind along the way. Uh, thanks, guy. I myself used to say, with the self-deprecating humor for which I am justly renowned, that it was the kind of book John O’Hara might have written if he’d had no talent. I’ve come to regard that judgment as unfair, but if you substitute “scruples” for “talent,” I suppose the comment could stand.

Jill’s next book, The Trouble With Eden, was supposed to be a hardcover bestseller. That was Berkley’s idea; they asked for a big Peyton Place kind of novel, and I wrote one set in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where I’d had the bad judgment to open an art gallery, and the good sense a year later to close it. It got a very strange review in Esquire, where the reviewer said he thought when he started it that it was really quite good, but changed his mind along the way. Uh, thanks, guy. I myself used to say, with the self-deprecating humor for which I am justly renowned, that it was the kind of book John O’Hara might have written if he’d had no talent. I’ve come to regard that judgment as unfair, but if you substitute “scruples” for “talent,” I suppose the comment could stand.

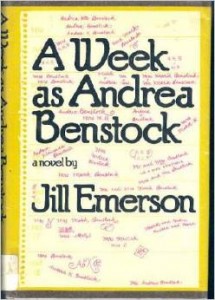

Finally, a lunch with the Peggy Roth, then editor-in-chief at Dell, led me to write a novel set in the Jewish community in my hometown of Buffalo. I’d never done this before, and characteristically I felt the need to bring out A Week as Andrea Benstock under a pen name. (The titular protagonist is a  woman, so I told myself a female pen name would be commercially advantageous, but I know now that wasn’t my real reason.) The structure was suggested by a Georges Simenon novel called Four Days in a Lifetime, which I’d read but of which I recalled nothing beyond the fact that the narrative was limited to four separate and significant days in the lead character’s life.

woman, so I told myself a female pen name would be commercially advantageous, but I know now that wasn’t my real reason.) The structure was suggested by a Georges Simenon novel called Four Days in a Lifetime, which I’d read but of which I recalled nothing beyond the fact that the narrative was limited to four separate and significant days in the lead character’s life.

My novel picks out seven representative days over ten years. I think it’s a good piece of writing, and so did Donald I. Fine at Arbor House, who wanted to publish it, and who was astonished when I showed up to keep his appointment with Jill Emerson. He pleaded with me to use my own name, but I was adamant; I could always be counted on to take a stand so long as it was not in my own best interests. Don managed to sell the book to Redbook for serialization, and wasn’t Jill chuffed at that?

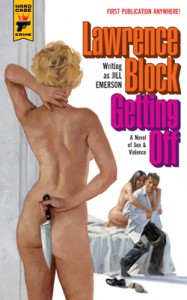

Finally, in 2012 Charles Ardai at Hard Case Crime published my new novel, Getting Off, with the undebatable subtitle “a novel of sex and violence.” I felt it was a good fit with Jill’s body of work, and decided accordingly on an open pen name: “By Lawrence Block writing as Jill Emerson.”

Finally, in 2012 Charles Ardai at Hard Case Crime published my new novel, Getting Off, with the undebatable subtitle “a novel of sex and violence.” I felt it was a good fit with Jill’s body of work, and decided accordingly on an open pen name: “By Lawrence Block writing as Jill Emerson.”

The combination of pen name and publisher led some readers to assume it was an old book brought back to life, which was by no means the case. Kit Tolliver is very much today’s woman, and she could never have been written in the last millennium. And the book did draw attention to Jill’s earlier work, which was certainly a Good Thing.

The links here are all to Amazon, where Kindle Unlimited members can scoop up the first seven titles free of charge. (I know, it’s remarkable. And yes, I get paid, even if you don’t pay a cent. Neat, huh?) Getting Off is $6.99 as an ebook, a few dollars more in paperback. But if you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber, you can get the book free in installments. I’ve self-published it in twelve sections, priced at $2.99 each, which is way too expensive…but KU subscribers can pick up all 12 free of charge and get the whole book that way. (“There are tricks and shortcuts in every trade but mine,” said the carpenter, hammering a screw.) They’re numbered, to make it easy to read them in order.

All of Jill Emerson’s ebooks are available, via Open Road, on all ePlatforms. I’m sure you can find your own way to them, and I’ll stop here, as I’ve already devoted more of my Sunday to this post than I’d intended.

Cheers!

UNEQUIVOCALLY. THE. GREATEST. BLOG POST. EVER.