Given the number of comments and questions I get on this topic, a website page dedicated to it would seem long overdue. So let’s see how it goes. (And Joe, I know you’re getting anxious to close…) I’ll start, if it’s all the same to you, with films with which I have no connection whatsoever.

There is a screenwriter by the name of Lawrence J. Block whose credits include The Funhouse (1981) and Captain America (1990). You can learn more about his work on his IMDb page, and will see that he is not me. There is also…

LAWRENCE JOEL “LARRY” BLOCK (October 30, 1942 – October 7, 2012)

This Lawrence Block was an actor who lived in New York and appeared frequently in films, on television, and on the stage. He almost always used the name “Larry Block.” You can find out more about his acting career on his Wikipedia page.

My own middle initial, which appears few places besides my tax returns and passport, is R. Friends do call me Larry, but I’ve never used it on a piece of writing. It’s always plain old Lawrence Block.

So there.

I first became aware of LJB in the early 70s, when I had an apartment on the Upper West Side. We both had listed phones, and each of us occasionally got a call meant for the other. “No, you want Larry Block the hack writer,” he told at least one caller, who reported as much to me with something approaching glee. I decided to tell the next clown with a wrong number that he wanted Larry Block the ham actor, but I never got the chance.

I saw him once on stage, in some off-off-Broadway effort on West 42nd Street, and I saw him on the screen, in a non-porn role in a porn film, The Devil in Miss Jones. (A good friend of mine, the late Patrick Farrelly, also had a non-porn role in the film. I can’t find either of them listed in the credits, so they may have used other names, or been in another film altogether. Never mind.)

And I once met him face to face, although he never knew it.

I was walking with a writer friend, Thomas Cook. We’d been at a group dinner in midtown, and I was walking Tom home to his apartment in Hell’s Kitchen, and would then walk myself home to my place in the Village. Tom had previously mentioned that he had a friend with the same name as I, actor Larry Block, and as we walked west on 46th Street he said, “Oh, there he is now.”

I forget what LJB was doing. Lugging garbage cans to the curb, I think, or lugging them back. Never mind.

“I’ll introduce you,” Tom said. And, as we drew up to where my namesake was lugging something or other, he said brightly, “Larry Block, meet Larry Block.” Larry Block the actor assumed Tom had just said his name twice, and had not bothered saying the name of his companion, and I don’t think he cared a whole lot anyway. Whereupon Tom and I continued our walk, and Tom clearly thought he’d successfully introduced the two of us, and I didn’t care enough to let him know what had happened.

Then a couple of years later Larry Block died.

But his work lives on, at least to the extent that it keeps turning up in lists of my work. I don’t believe for a moment that this blog post will straighten things out. But, you know. We do what we can.

Let’s move on, shall we? To—

MY SO-CALLED SCREENWRITING CAREER

I’ve been a member of Writers Guild of America—East for many years, and somehow did enough work to qualify for a small pension, for which I give thanks once a month. I also served on that organization’s executive board, or whatever they called it, but for less than a year; “Larry works and plays well with others” is something no teacher ever wrote on my report card. They were very nice folks, my colleagues on the board, but it didn’t take me too long to realize that I was, um, miscast.

I’ve been a member of Writers Guild of America—East for many years, and somehow did enough work to qualify for a small pension, for which I give thanks once a month. I also served on that organization’s executive board, or whatever they called it, but for less than a year; “Larry works and plays well with others” is something no teacher ever wrote on my report card. They were very nice folks, my colleagues on the board, but it didn’t take me too long to realize that I was, um, miscast.

Most of my screenwriting wasn’t miscast. Indeed, it never got cast at all. Writing for the shelf is how screenwriters characterize work for which they get paid but which never gets shot, and that pension would not be mine but for my own writing for the shelf. There wasn’t all that much of it, but the most noteworthy item on that shelf would be Keller, a screenplay based on the first book in that series, Hit Man. It went through a couple of drafts and a polish, and was shopped around with a lead actor (Jeff Bridges) and a director (Martin Bell) attached, and it lingered for a few years, and somehow it never quite got made. I wish it had, as I liked the way the screenplay turned out, but it didn’t.

Next up was Tilt!, An original dramatic series centered on big-time poker, developed for ESPN by Brian Koppelman and David Levien, who wrote and directed Rounders. I was in the writers room from the beginning, and the ritual of getting up in the  morning and going to an office five days a week was something I hadn’t experienced since I worked at Western Printing in Racine for a year and a half in the mid-60s. I enjoyed it quite a lot, and actually did work and play reasonably well with others, and wound up writing two scripts, with a solo credit for Episode 4 and a shared credit for Episode 5.

morning and going to an office five days a week was something I hadn’t experienced since I worked at Western Printing in Racine for a year and a half in the mid-60s. I enjoyed it quite a lot, and actually did work and play reasonably well with others, and wound up writing two scripts, with a solo credit for Episode 4 and a shared credit for Episode 5.

Tilt! was a pretty good series, and a survey of viewers who actually saw it showed that they liked it quite a bit. But there were never very many of them; the experiment failed largely because, while fans tuned in to ESPN to watch people playing real poker, they weren’t much interested in watching fictional poker. There were creative problems as well, but they were the least of it. Tilt! simply never attracted enough viewers to make the ESPN guys happy, and it went to TV Heaven after a single nine-episode season.

In an earlier age, that would have been the end of it—but nowadays you can find virtually anything on DVD, and this link will take you to the Amazon page.

***

Wong Kar-Wai, the brilliant Chinese filmmaker, was a fan of my Matthew Scudder novels for years, and said so in at least one interview that came my way. He got in touch, and we met, and discussed various projects, none of which ever got off the ground. One was going to take place in Shanghai in the late 1930s, and would star Nicole Kidman, and why WKW thought I was the right person to write it is beyond me. My wife and I got a trip to Shanghai and Hong Kong out of the deal, for reasons that are equally elusive, and nothing quite came of it.

And then he sent me an eight-minute film of his, in Chinese and with Chinese actors, in which a young woman drops into the deli  across the street from her apartment, eats some blueberry pie, and explains she’s through with her husband/lover/whatever. She hands the clerk her keys, and he puts them in a jar filled with people’s keys. Evidently more people give this dude their keys than buy his blueberry pie.

across the street from her apartment, eats some blueberry pie, and explains she’s through with her husband/lover/whatever. She hands the clerk her keys, and he puts them in a jar filled with people’s keys. Evidently more people give this dude their keys than buy his blueberry pie.

WKW wanted this snippet to be the basis of his first-ever English-language film, which he intended to shoot in America. My Blueberry Nights would be the title, and it would start in the deli, with the blueberry pie and the keys-in-the-jar. But instead of dropping off her keys and going home, or whatever she did exactly in the Chinese version, our heroine would travel all over the country, having adventures here and there, before ultimately returning and reclaiming her keys from the deli guy. As for what would happen in her various adventures, and where they’d take place, well, that was To Be Determined.

Oh, one more thing. He already knew he wanted Norah Jones to play the lead. Never mind that she’d never acted, except perhaps in a grade-school play. He knew she could do it.

Wong Kar-wai makes some of the most beautiful films in cinema history. He has an amazing visual sense and it works superbly on the screen. Dialogue and story, on the other hand, are every much on the other hand. I was supposed to write a script, and what I learned in time was that the man had never worked from a script. A couple of pages of notes was all he ever used. His actors improvised their own lines, and the story changed from moment to moment. This made working with him an interesting experience, as he kept changing his mind as to where the scenes would be set, and what would happen, and who these people were, and, oh, pretty much everything.

Still, it came out looking gorgeous, and some fine actors did some fine work—Natalie Portman, Rachel Weisz, David Strathairn. When did any of those three ever fail to do fine work? Norah Jones was in over her head, she appeared in just about every scene, and how could anyone expect her to carry a whole film? But she did what she could. I don’t know why the hell he didn’t give her something to sing.

Worth your time. And now when you can own it for less than it would cost to see it in a theater, well…

FILMS BASED ON MY WORK

Deadly Honeymoon was a high-concept book, although I’m not sure the term was in vogue when it was written. What it means is the premise can be summed up in a sentence or two, simple enough for the suit at the studio to grasp. The premise in this instance was that a young Just-Married couple,complete with Virgin Bride (well, this was 50+ years ago, and while I didn’t know any virgin brides, I had it on good authority that they existed) are about to consummate their marriage in a resort hotel they’ve chosen for their honeymoon. They are witnesses to a gangland homicide, and almost as an afterthought the thugs rape Our Girl, and the rest of the book is a story of revenge sought and achieved.

Deadly Honeymoon was a high-concept book, although I’m not sure the term was in vogue when it was written. What it means is the premise can be summed up in a sentence or two, simple enough for the suit at the studio to grasp. The premise in this instance was that a young Just-Married couple,complete with Virgin Bride (well, this was 50+ years ago, and while I didn’t know any virgin brides, I had it on good authority that they existed) are about to consummate their marriage in a resort hotel they’ve chosen for their honeymoon. They are witnesses to a gangland homicide, and almost as an afterthought the thugs rape Our Girl, and the rest of the book is a story of revenge sought and achieved.

See? High concept. It is in fact a terrific premise, and I wish I’d thought of it. But I didn’t. My very close friend Donald E.Westlake did. He told me his idea, and I waited for him to write it, and the months passed. And I couldn’t get the idea out of my head. So I called Don and asked him if he’d every done anything with the idea. He said he hadn’t. Was he likely to? He said probably not. Well, in that case did he mind if I took a shot at it?

“Be my guest,” he said.

“Be my guest,” he said.

So I wrote the book. When Don read it, he was surprised I had the bride and groom team up to track down the killers. He’d figured the husband would stash the wife somewhere safe and take care of things on his own. For my part, I had assumed Don’s original idea was for the two to work together, so I was adding a new wrinkle without realizing it was new.

Never mind. Macmillan published the book in 1967, my first hardcover sale. (A step up, everybody thought; in fact it was offered to Macmillan because Gold Medal, the paperback house, read it and turned it down.) It didn’t sell many copies, but film people were predictably crazy about the idea, and it kept getting optioned, and screenwriters kept doing treatments and scripts, and I was making a nice living from the thing until somebody ruined everything by making a film.

And ruined is the operative word. They changed the title to Nightmare Honeymoon, which may or may not have been an  improvement, and then they sighed and shook their heads. For quite a while the movie went unreleased. Then a friend saw it as an in-flight movie, carrying the notion of a captive audience to something of an extreme, and then in 1975 when I was driving to California I saw it on a moviehouse marquee in downtown Las Vegas; it was paired with a film called Snuff—I’m not making this up—and Nightmare Honeymoon got second billing.

improvement, and then they sighed and shook their heads. For quite a while the movie went unreleased. Then a friend saw it as an in-flight movie, carrying the notion of a captive audience to something of an extreme, and then in 1975 when I was driving to California I saw it on a moviehouse marquee in downtown Las Vegas; it was paired with a film called Snuff—I’m not making this up—and Nightmare Honeymoon got second billing.

Something—I choose to believe it was God—kept me from buying a ticket. I did see the film a few years later on late-night television, and only watched some of it. I watched a little more on another occasion.

Hey, maybe you’ll like it. Maybe it’s better than I think. What do I know?

As far as that goes, if you’d like to see what got top billing, well, have a look at Snuff. But if you think it’s terrific, just keep it to yourself. Fair enough?

***

Eight Million Says to Die was the fifth book about Matthew Scudder, and you could say it was more ambitious than the four preceding it. Very long for a detective novel at 120,000 words, it had three themes—the solution of the murder of a call girl, the mortal peril of life in a big city (or indeed anywhere), and the protagonist’s efforts to come to terms with his own alcoholism. It got a good reception, was shortlisted for the Edgar award, and won the Shamus. It has never been out of print since Arbor House brought it out in 1982.

Eight Million Says to Die was the fifth book about Matthew Scudder, and you could say it was more ambitious than the four preceding it. Very long for a detective novel at 120,000 words, it had three themes—the solution of the murder of a call girl, the mortal peril of life in a big city (or indeed anywhere), and the protagonist’s efforts to come to terms with his own alcoholism. It got a good reception, was shortlisted for the Edgar award, and won the Shamus. It has never been out of print since Arbor House brought it out in 1982.

It was a year or two later that Oliver Stone decided to option it, with the intention of writing a screenplay and directing the film. He was in town, and wanted to meet with me to discuss the project. We met at Jimmy Armstrong’s saloon, the real-life hangout of the fictional Matt Scudder. I’m not sure which of us suggested the venue.

I believe Lynne and I were married by then. In any event, she came along with me, and Oliver showed up, suffering the effects of either jet lag or the use of a substance that very likely originated in Colombia. Either way, he was wired and tired, and disconcerting company. I don’t remember much of our conversation, but do recall that he wanted to open the story up, whatever that means, and felt Scudder needed a Mr. Big as an adversary. Someone like Al Pacino’s character in Scarface, I suppose. Oliver had written that movie, Brian De Palma directed it—and now Stone could demonstrate his ability to do the job as effectively as De Palma, with (if he had anything to say about it) essentially the same movie.

So he wanted to change the story—which is okay, that’s what happens in movies—but he also wanted me to collaborate with him and help him make these changes. He said he thought I’d be the perfect person to do it, and I said I was the worst person in the world to do it, because we already knew what I thought the story was. We shook hands, and Oliver picked up the check, and Lynne and I went home, telling each other I’d shown wisdom beyond my years in turning down the opportunity to work on the screenplay.

So he wanted to change the story—which is okay, that’s what happens in movies—but he also wanted me to collaborate with him and help him make these changes. He said he thought I’d be the perfect person to do it, and I said I was the worst person in the world to do it, because we already knew what I thought the story was. We shook hands, and Oliver picked up the check, and Lynne and I went home, telling each other I’d shown wisdom beyond my years in turning down the opportunity to work on the screenplay.

Well, I’m not so sure. God knows I didn’t know how to write a screenplay at the time, but few of us are born with such knowledge, and this would have been a good way to start learning. It also would have been decent pay—Guild minimum at a minimum, so to speak. And it would have been a dandy credit. But I was being true to myself, I suppose. Or scared. Or both.

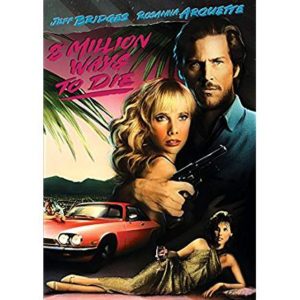

Oliver drafted a screenplay, and I received a copy of it. I didn’t think much of it. It was set in New York, and there was a drug trafficker who served as Scudder’s adversary. Then I lost track of things—it never occurred to me to pay much attention—and next thing I knew was Oliver had moved on to other things, notably Platoon. But a film company was persisting with the movie. They wound up shooting it in Los Angeles, and I happened to be out there at the time; Lynne and I flew out for my friend Hal Dresner’s wedding, for which I was miscast as Best Man, and one morning during our stay we visited the set somewhere in El Segundo. I took a picture with Jeff Bridges, who played Scudder, and chatted some with Alexandra Paul, who played Sunny. I may have met Rosanna Arquette, but  I can’t say for sure. I do remember somebody taking me to meet Hal Ashby at his trailer, Various substances had taken their toll over the years, and he struck me as the saddest man I’d ever met.

I can’t say for sure. I do remember somebody taking me to meet Hal Ashby at his trailer, Various substances had taken their toll over the years, and he struck me as the saddest man I’d ever met.

A film set is not an exciting place to be. Nothing happens at great length. We hung around for an hour or two and departed, and the next thing I knew of the film was when they released it in theaters.

I didn’t like it. They’d taken a quintessential New York story and set it in California, and while you can do that and still wind up with a good picture, that’s not what happened. I didn’t like it, and I was by no means alone in that judgment. Filmgoers went to other films instead. Critics panned it. According to Wikipedia, the film got a positive rating of 0.00 on Rotten Tomatoes.

There were a lot of things wrong with the movie, and it’s not my job to point them out to you. Jeff Bridges told me it’s a movie he wishes he had back, that they all did good work in the film but that the studio took the final cut away from Ashby and used the less successful takes. They almost changed the title, since “Eight Million” doesn’t have anything much to do with Southern California, but they compromised by changing the first word to a numeral. 8 Million Ways to Die. Ah yes. Makes all the difference in the world.

And I don’t really want to badmouth the picture. After all, it and Burglar paid my mortgage. And there were things to like in it; Jeff Bridges gave a strong performance, as did Andy Garcia in his first starring role. I’ve met some people who like the film,although I don’t believe I’ve met any fan of the film who’d read the book first.

One thing with which the film did provide me was a remarkably surreal moment. In 1991 my wife and I had perhaps our greatest adventure, walking from Toulouse over the Pyrenees and along the ancient pilgrimage route  to Santiago de Compostela. Some of our days were merely tiring, while others were flat-out exhausting. On one of the latter variety, we stumbled into an inn in Navarre, dropped our bags in our room, and went downstairs to the restaurant. While we waited for our bocadillos de queso, we looked across at the TV, where 8 Million Ways to Die, dubbed in Spanish, had just begun playing. Once we’d established that it was not an hallucination, we found ourselves equally incapable of watching it or ignoring it. I have to say, though, that the dubbing helped. It was easier for us to take if we couldn’t understand what they were saying.

to Santiago de Compostela. Some of our days were merely tiring, while others were flat-out exhausting. On one of the latter variety, we stumbled into an inn in Navarre, dropped our bags in our room, and went downstairs to the restaurant. While we waited for our bocadillos de queso, we looked across at the TV, where 8 Million Ways to Die, dubbed in Spanish, had just begun playing. Once we’d established that it was not an hallucination, we found ourselves equally incapable of watching it or ignoring it. I have to say, though, that the dubbing helped. It was easier for us to take if we couldn’t understand what they were saying.

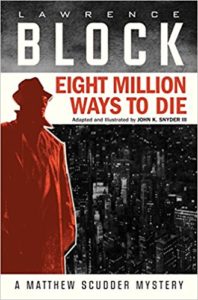

While there’s been occasional talk of remaking the movie, nothing’s ever come of it. It would be nice if they got it right—and John K. Snyder III has demonstrated convincingly how to do just that. Not as a film, but as a stunning graphic novel. In this medium that’s hugely different from prose fiction, JKS3 has managed to fit the whole story very neatly into a compact space, without losing much of anything. And he kept the story in New York, and in 1982, and…well, this isn’t the place to sell you on it. But you might want to give it a look, especially if you are or would like to be a screenwriter.

***

8 Millions Ways to Die was widely regarded as an artistic and commercial failure. Burglar, on the other hand, was that and more. It was a travesty.

When the picture was made, I’d written five books about Bernie Rhodenbarr, a burglar and bookseller who lived and worked in New York. (There have been six more since then, most recently The Burglar Who Counted the Spoons.) Now I rarely know too much about what my characters look like, especially those characters through whom the story is told. Even now, I couldn’t tell you the color of Bernie’s eyes or hair, and I’ve never specified—or known, actually—just how old he is. (Whatever his age may be, I do know that it doesn’t change. Matthew Scudder has aged in real time, and is changed by experience; Bernie remains essentially the same. I’ve made the Scudderian mistake myself of aging in real time, and I don’t recommend it.)

When the picture was made, I’d written five books about Bernie Rhodenbarr, a burglar and bookseller who lived and worked in New York. (There have been six more since then, most recently The Burglar Who Counted the Spoons.) Now I rarely know too much about what my characters look like, especially those characters through whom the story is told. Even now, I couldn’t tell you the color of Bernie’s eyes or hair, and I’ve never specified—or known, actually—just how old he is. (Whatever his age may be, I do know that it doesn’t change. Matthew Scudder has aged in real time, and is changed by experience; Bernie remains essentially the same. I’ve made the Scudderian mistake myself of aging in real time, and I don’t recommend it.)

So what did I know about Bernie? Well, I knew he was a white male, probably the son of a Jewish father and a Gentile mother, and that while he may have been born elsewhere, he was very much a New Yorker.

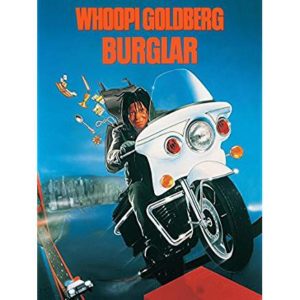

So it was kind of jarring to hear that he would be portrayed on film by Whoopi Goldberg.

If you wonder how this came about, you are not alone. It’s a question I’m often asked, so let me answer it. When my agent made a deal with Nelvana for movie rights to the Burglar books, no casting decisions had been made. Then there came a time when Bruce Willis was the leading contender for the title role. This was years before the  Die Hard films, and Willis was emerging as a star in the TV series Moonlighting, where he played a wisecracking urban private detective; it wasn’t a stretch to see him as Bernie, with Whoopi as his best friend Carolyn Kaiser, a lesbian dog groomer. (That’s ambiguous, isn’t it? Let me say by way of clarification that Carolyn’s a lesbian who grooms dogs, not a groomer of lesbian dogs. Never mind.)

Die Hard films, and Willis was emerging as a star in the TV series Moonlighting, where he played a wisecracking urban private detective; it wasn’t a stretch to see him as Bernie, with Whoopi as his best friend Carolyn Kaiser, a lesbian dog groomer. (That’s ambiguous, isn’t it? Let me say by way of clarification that Carolyn’s a lesbian who grooms dogs, not a groomer of lesbian dogs. Never mind.)

Then one day Willis was out. (Maybe he got a look at the script.) And, the way I heard it, Whoopi popped up and said, “I can do that.” (This, I’ve heard, has been a frequent response of hers; she always thinks she can do it, whatever it is. And, by golly, she’s usually correct.)

The producers decided she was right. So she got the part, and Bobcat Goldthwaite was cast as the dog groomer sidekick, and somebody gave the existing script a sex-change operation. They moved the bookstore from New York to San Francisco, perhaps because someone in the production company had left his heart there, along with his better judgment.

Here’s the thing. You can change just about anything, including the race and sex of the main character, and still make a good movie. It won’t be faithful to the original source, but so what? When you’re in charge of a film with a seven- or eight-figure budget, fidelity to your source material is a low priority—and so is making its author happy. What you want to do is wind up with something that’ll induce people to line up and buy tickets.

Here’s the thing. You can change just about anything, including the race and sex of the main character, and still make a good movie. It won’t be faithful to the original source, but so what? When you’re in charge of a film with a seven- or eight-figure budget, fidelity to your source material is a low priority—and so is making its author happy. What you want to do is wind up with something that’ll induce people to line up and buy tickets.

And I’d have been fine with that. The books still existed just as I had written them, and a successful film would induce more people to buy them, and what’s so bad about that?

Alas, the movie wasn’t good. The story was that of the second book in the series, The Burglar in the Closet, with elements of The Burglar who Liked to Quote Kipling, and if anything the movie was too faithful to the book’s storyline, if to nothing else. The script was weak, the pace was off, and I personally find the onscreen presence of Bobcat Goldthwaite several orders of magnitude beyond irritating. Whoopi did what she could with what they gave her, and she was probably the best thing about the film, but she couldn’t save it. Roger Ebert described the film as “a witless, hapless exercise in the wrong way to package Goldberg. This is a woman who is original. Who is talented. Who has a special relationship with the motion picture comedy. It is criminal to put her into brain-damaged, assembly-line thrillers.”

Oddly, the film wasn’t that far from commercial viability. Audiences would laugh while they watched it, then tell their companions on the way out that it wasn’t much good. And they were not being hypercritical. Some of the gags are funny enough to get you laughing, but you never quite manage to lose sight 0f the fact that what you’re watching is crap.

***

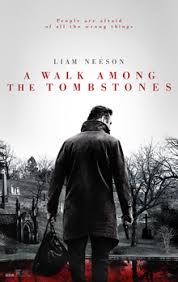

A Walk Among the Tombstones, the tenth Matthew Scudder novel, was published by William Morrow in 1992. A few years later it came to the attention of Scott Frank, who wanted to adapt it for the screen. Ans the next thing you knew it was playing at a theater near you.

A Walk Among the Tombstones, the tenth Matthew Scudder novel, was published by William Morrow in 1992. A few years later it came to the attention of Scott Frank, who wanted to adapt it for the screen. Ans the next thing you knew it was playing at a theater near you.

Well, not quite.

A deal came together, and a company optioned film rights to the book and engaged Scott to write the screenplay. He did so, setting the story in 1998, and making a variety of structural changes to the story over the course of several rewrites. Eventually it looked as though, after quite a few years, the film was actually going to be made. Harrison Ford, an eminently bankable actor, would star as Matthew Scudder.

And then quite suddenly, just weeks before the announced commencement of principal photography, it all fell apart. Harrison Ford walked away from the picture. As I understand it, he didn’t want to work with the chosen director, and that was the end of that.

Except it wasn’t. They extended the option a couple of times, and then they decided they were tired of pounding sand down that particular rathole. The option lapsed and the whole project was dead.

Except it wasn’t. They extended the option a couple of times, and then they decided they were tired of pounding sand down that particular rathole. The option lapsed and the whole project was dead.

Well, not quite. A faint pulse beat on. Scott still wanted to make the picture, and eventually things came together again. Liam Neeson, to my mind a perfect choice, was cast as Scudder. Scott Frank had decided he wanted to direct the picture as well. He shot it, remarkably enough, in New York, where it was set, and the climactic scene was indeed set in Green-Wood Cemetery. I got to be present for the shooting of certain scenes—Scudder’s meeting with TJ (Brian Baxter) in the New York Public Library and a later scene (shown here) of the two of them in a diner, and Scudder’s phone conversation with the villains. And I even had a non-speaking appearance, as Third Man at Bar, in a scene that, alas, didn’t make the cut. It was a scene featuring Ruth Wilson, and when her part got chopped out of the movie, so did mine. I suspect it was more upsetting for her than it was for me.

And, in the fall of 2014, the film was released.

It didn’t do much business, not nearly enough to induce Universal to greenlight a sequel, and there were a few reasons for this. A big one was that Liam Neeson, notwithstanding the absolute excellence of his performance,  was identified in the public mind as the star of the Taken films. People who wanted more of the same were disappointed by this more thoughtful and less action-packed film. And other filmgoers, those who weren’t interested in an action movie, similarly assumed that was what they were likely to get—and stayed away.

was identified in the public mind as the star of the Taken films. People who wanted more of the same were disappointed by this more thoughtful and less action-packed film. And other filmgoers, those who weren’t interested in an action movie, similarly assumed that was what they were likely to get—and stayed away.

I liked a whole lot about the movie, and I disagreed with many of the changes Scott made to the plot. To my mind the denouement was a cliché, as was the pop-up confrontation with another investigation. (Gee, we’ve never seen that before.) But of course I liked the book better. What would you expect? I wrote the thing.

The IndieWire website has a much better analysis of the book-to-film aspects of A Walk Among the Tombstones, and you may want to have a look. It told me some things I hadn’t known. I’ll include their final paragraph here, as it sums things up nicely:

“As for which is ‘better,’ it’s a bit of an unfair question to ask. Block has all the freedom in the world on the page that Frank doesn’t have on the screen, and so we’d say the writer/director did the best he could with what were likely some stringent parameters and expectations he had to hit. For our money, we’d say for the full Scudder experience you’ll want the book, but as an abridged version, the film does an adequate if not wholly satisfying job.”

***

I’ve also had some works adapted for short films and TV, but they’ll have to wait until I find time to update this page…