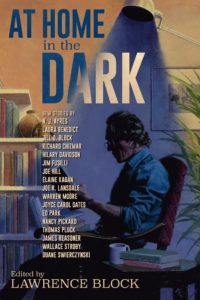

My foreword to At Home in the Dark has been getting some attention, and I thought some of you might enjoy having a look at it. And if it should induce you to order the anthology, well, so much the better!

IT’S GETTING DARK IN HERE

Ages ago, Lucille Ball had this exchange on I Love Lucy with a snobbish character whose task it was to elevate her culturally:

SNOB: “Now there are two words I never want to hear you say. One is Swell and the other is Lousy.”

LUCY: “Okay. Let’s start with the lousy one.”

Funny what lingers in the mind…

Every year or so, I stub my toe on a couple of buzzwords and decide I’d just as soon not encounter them again. There are two that I’ve found increasingly annoying of late, and if Lucy were here I’d tell her that one of them is Awesome and the other is Iconic.

It is in the nature of the spoken language for words to come and go, and none are more cyclical than those we choose to indicate strong approval or disapproval. ’Swonderful, Cole Porter told us, that you should care for me. Indeed, ’Smarvelous, isn’t it? Wonderful, marvelous, terrific, sensational, excellent, brilliant—each takes its turn as a way of demonstrating great positive enthusiasm.

For quite a few years now, le mot du jour has been awesome. Now it’s a perfectly reasonable word, and means simply that the noun thus modified is likely to inspire awe, even as that which is wonderful is clearly full of wonder. If everything thus described is truly awesome, one is left to contemplate a generation of wide-eyed and slack-jawed folk gaping at all that is arrayed in front of them.

Well, okay. Periodically a word of approval swims upstream into the Zeitgeist, resonates with enough of us to have an impact, and becomes the default term for us al—or at least those of us under forty. Before too long its original meaning has been entirely subsumed, and all it means to call something awesome is that one likes it.

Deep down where it lives, awesome is essentially identical in meaning to awful. And there was a time when awful and wonderful were synonyms—full of awe, full of wonder. Now, as Lucy could tell you, one is swell and the other is lousy.

If anything good is awesome, then anything memorable or distinctive is iconic. I shouldn’t complain, I don’t suppose, as several of my own books have had that label applied to them, and perhaps I ought to regard the whole business as awesome. But iconic ? Really? No narcissist thinks more highly of his own work than I, but I have trouble picturing any of my books as a literal icon, displayed on the wall of a Russian Orthodox cathedral.

Wait, let me rethink that. Maybe Eight Million Ways to Die might make the cut. I mean, dude, that book is awesome.

Never mind. I have the honor to present to you seventeen stories, any or all of which you might well describe as awesome or iconic or both. And I want to introduce them by pointing out another buzzword, one of which I’ve tired at least as much as I have of the two of them combined.

Noir.

It’s a perfectly good word, and particularly useful if you’re in Paris and an ominous feline crosses your path. “Un chat noir!” you might say—or you might offer a Gallic shrug and pretend you hadn’t seen it. Whatever works.

It’s a perfectly good word, and particularly useful if you’re in Paris and an ominous feline crosses your path. “Un chat noir!” you might say—or you might offer a Gallic shrug and pretend you hadn’t seen it. Whatever works.

Noir is the French word for black. But when it makes its way across la mer, it manages to gain something in translation.

Early on, it became attached to a certain type of motion picture. A French critic named Nino Frank coined the term Film Noir in 1946, but it took a couple of decades for the phrase to get any traction. I could tell you what does and doesn’t constitute classic film noir, and natter on about its visual style with roots in German Expressionist cinematography, but you can check out Wikipedia as well as I can. (That, after all, is what I did, and how I happen to know about Nino Frank.)

Or you can read a recent novel of mine, The Girl With the Deep Blue Eyes. The protagonist, an ex-NYPD cop turned Florida private eye, is addicted to the cinematic genre. When he’s not acting out a role in his own real-life Film Noir, he’s on the couch with his feet up, watching how Hollywood used to do it.

That’s what the French word for black is doing in the English language. It’s modifying the word film, and describes a specific example thereof.

Now though, it’s all over the place.

The credit—or the blame, as you prefer—goes to Johnny Temple of Akashic Books. In 2004 Akashic published Brooklyn Noir, Tim McLoughlin’s anthology of original crime stories set in that borough. They did very well with it, well enough to prompt McLoughlin to compile and Akashic to publish a sequel, Brooklyn Noir 2: The Classics, consisting of reprint. It did well, too, and a lot of publishers would have let it go at that, but Akashic went on to launch a whole cottage industry of darkness.

A look at the publisher’s website shows a total of 120 published and forthcoming Noir titles, but the number is sure to be higher by the time you read this. Akashic clearly subscribes to the notion that every city has a dark side, and deserves a chance to tell its own stories.

It is, I must say, a wholly estimable enterprise. I could not begin to estimate the number of writers whose first appearance in print has come in an Akashic anthology. They owe Akashic a debt of gratitude, as does a whole world of readers.

And as do I. I had the pleasure of editing Manhattan Noir and Manhattan Noir 2, and while neither brought me wealth beyond the dreams of avarice, each was a source of personal and artistic satisfaction. And, after I’d coaxed a couple friends into writing stories for my anthology, I could hardly demur when they turned the tables on me. I’d written one myself for Manhattan Noir, and wrote another for S. J. Rozan’s Bronx Noir, and a third for Sarah Cortez and Bootsie Martinez’s Indian Country Noir. All three were about the same cheerfully homicidal young woman, and although she didn’t yet have a name, she clearly had a purpose in life. I found more stories to write about her, realized they were chapters of a novel in progress, and in time Getting Off was published by Hard Case Crime.

So I wish their series continued success. Although their stories have never had much to do with Hollywood’s 1940 vision of noir, neither are they happy little tales full of kitty cats and bunny rabbits. They are serious stories, taking in the main a hard line on reality, and any gray scale would show them on the dark end of the spectrum.

Noir? Noirish? Okay, fine. I’m happy for them to go on using the word. In fact I’m all for letting them trademark it, just so the rest of the world could quit using it.

That, Gentle Reader, is a rant. And you can relax now. I’m done with it.

So here we have seventeen stories, and you’ll note that they cover a lot of ground in terms of genre. Most are crime fiction to a greater or lesser degree, but James Reasoner’s is a period Western and Joe Hill’s is horror and Joe R. Langdale’s is set in a dystopian future, and what they all have in common, besides their unquestionable excellence, is where they stand on that gray scale.

They are, in a word, dark.

And that, I must confess, is the modifier I greatly prefer to noir.

It’s easy to see I’m partial to it. A few years ago I put together a collection of New York stories for Three Rooms Press, and the title I fastened upon was Dark City Lights. (While I was at it I fastened as well upon some of that book’s contributors; of the writers in At Home in the Dark, six of them—Ed Park, Jim Fusilli, Thomas Pluck, Jill D. Block, Elaine Kagan and Warren Moore—wrote stories for Dark City Lights.)

The title came to me early on. Years ago I’d come across O. Henry’s last words, spoken on his deathbed, and in case you missed them in the epigraph, you needn’t flip pages. “Turn up the lights,” said the master of the surprise ending. “I don’t want to go home in the dark.”

I can but hope you enjoy At Home in the Dark. I find it’s inspired me, and there’s another anthology taking shape in my mind even now. I already have a title in mind, and it’s five words long (as my titles tend to be), and it has the word dark in it.

Trust me. It’ll be awesome.

At Home in the Dark, with stories by Noreen Ayres, Laura Benedict, Jill D. Block, Richard Chizmar, Hilary Davidson, Jim Fusilli, Joe Hill, Elaine Kagan, Joe R.Lansdale, Warren Moore, Joyce Carol Oates, Ed Park, Nancy Pickard, Thomas Pluck, James Reasoner, Wallace Stroby, and Duane Swierczynski, was published as a deluxe limited hardcover edition by Subterranean Press; those hardcover copies are long gone, but the book’s available now as an ebook or trade paperback.

It seems to me that the (over) popular usage of “awesome” stems from after the introduction of the Datsun 240Z in 1970. A widely aired advertisement showed the vehicle with an announcer intoning “awesome!”.

FWIW, “Old School” only became popular, especially among “urban youth” (as “o skoo”) following the release of the motion picture in 2003.

I may well be mistaken in either or both cases

You could be right.

LB, of all the authors I have read in my many years, and I have read a few, I have found none more deserving of this statement than you. Sir, you certainly have a way with words.

What a lovely compliment, Jean—thank you!