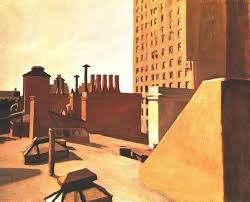

I’d hoped to persuade Gail Levin to provide an introduction for In Sunlight or in Shadow. As the editor of Hopper’s Catalogue Raisonné and the author of his definitive yet wonderfully readable biography, she seemed the perfect choice. She surprised me by offering to supply a story instead, and in due course delighted me with her first-ever work of fiction, referencing this 1932 painting, “City Roofs,” and spinning an artful story out of chilling fact.

THE PREACHER COLLECTS

by Gail Levin

They call me “Reverend Sanborn.” I was born Arthayer R. Sanborn, Jr., in 1916, in Manchester, New Hampshire, son of Arthayer and Annie Quimby Sanborn. I graduated from Gordon College, a good Christian school in Wenham, Massachusetts, and then from Andover Newton Theological Seminary. I served American Baptist Churches in Woodville, Massachusetts, and in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, before I went to Nyack, New York, where I led the First Baptist Church, located on North Broadway. My job came with the security of a home, just next to the church, where I lived with my wife, Ruth, and our four children.

Before long I met at church our neighbor and long-time parishioner, Marion Louise Hopper. An aging spinster, she lived alone in her family’s old house next door to the church. She liked to boast that her younger brother, and only sibling, was a famous artist, named Edward. Edward Hopper, however, appeared to want as little as possible to do with Nyack and his sister.

In early April 1956, Marion became ill and called Edward for help. He and his wife, Jo, had to rush up to Nyack from Manhattan. The doctor diagnosed Marion as having gallstones and a dangerous blood condition. She was then seventy-five and living in an old house with a decrepit furnace and water pipes that could scarcely do their job. The house was depressingly dark since Marion scrimped by using only twenty-five watt light bulbs. Her cat was emaciated and sick.

Her brother, just two years younger than his sister, found the role of rescuer disturbing. He complained that his ears had begun to ring; he ran to New York to see his own doctor, leaving Jo to deal with Marion. Jo found her sister-in-law disagreeable, complaining to me, “She and I make each other ill, we disturb each other so much.” Nothing serious was wrong with Edward, so he had to come back to Nyack to help Jo, check on Marion, and make sure that her furnace was working a late spring snowstorm struck. Jo, however, informed me that henceforth she expected Marion’s “noble” friends at church to prove their idea of worthiness. That is where I came into the picture.

Marion’s dependence on the church grew as she aged and became more feeble and reclusive. I saw to it myself that the church ladies auxiliary looked in on her as needed. But I also made a point of getting to know her myself. I had Marion give me the key to her house– just in case of an emergency. I got the idea to buy the poor shut-in a television set and soon she was hooked on watching soap operas. That got her off my back. While she was glued to the television set, I took it upon myself to explore the old house from top to bottom. I thought that I should check up on condition of the roof and so one day went up into the attic.

Looking around, I was surprised to find not leaks, but stacks and stacks of early art work by Edward Hopper: piles of drawings, oil paintings, and illustrations. After I returned several times and rummaged around, I found valuable historical documents including the letters young Edward had written to his family during the three trips he made to Europe just after completing art school. The more I learned the more I became concerned about what would happen to all these treasures after Marion’s death. Indeed, I could not get their fate off my mind. Marion’s only heirs were her brother and sister-in-law, and they were just a few years younger than Marion. None of them had produced any children, who could look after their estate.

I began to reflect that to save these art works from oblivion could not only be justified, but that the savior would be a hero. So I stepped up to prevent harm from coming to Hopper’s art works. I knew that vagrants might occupy an abandoned house. An empty house could be set on fire. The antique furniture and precious art works could be stolen, damaged, or destroyed. Marion certainly would not give me permission to remove these art works. They belonged to Edward. But he had all but abandoned them years ago, moving to New York. I alone cared for these art works more than anyone else in the world. I saw their value. I went to the library and read about Edward Hopper. I studied and made myself an expert. I researched the Hopper family’s genealogy, dating back to its arrival in 17th-century New Amsterdam.

As time went on, I found ways to make myself useful to Edward and Jo Hopper. For them, coming to Nyack from Manhattan was an unwelcome chore. It was nearly impossible during the half of the year that they spent living in South Truro on the far end of Cape Cod. When the old couple returned to New York City, late each October, they drove via Nyack, where Edward left their car at the family home. Only at this time and when they came to retrieve the car in the spring did they plan to see Marion. They were not close to her. She remained out of sight and forgotten.

Marion had little understanding of her brother’s life in New York. When he had a retrospective show at the Whitney Museum in 1964, she asked to attend the opening party and to bring her friend Beatrice and me. I was eager to go. But Edward, then eighty-two, could not be bothered by his sister’s request. He wrote to her: “This is the one time in the year when I can meet museum directors, critics and collectors of importance and I shall have to devote all my time to them (and will have no time for you, Dr. Sanborn and Beatrice.)” He was most ungrateful.

Still less did Edward have time to worry about the abandoned art works in the attic of his boyhood home. At first, I just rescued a few of the smaller drawings and paintings, taking them home to study…

##

Gail, who teaches at Baruch University, has written landmark works on Lee Krasner, Judy Chicago, and Theresa Bernstein, but is best-known for her extensive body of work centering on Edward Hopper. While many titles are out of print, they’re not impossible to find, and these links should prove fruitful:

Edward Hopper: The Art and the Artist. “This sumptuous book presents the full range of Edward Hopper’s work and offers greater access to Edward Hopper, the man, than any other single volume.”

Edward Hopper: The Complete Prints. “The text relevant and succinct and the printing beyond reproach. The perfect art book.”

Hopper’s Places. “Edward Hopper’s paintings, and photographs of the sites on which they are based, are the focus of Levin’s book. This comparative view illustrates Hopper’s compositional approach, his use of cropping, his exaggeration of the vertical or horizontal elements, and his simplifications, which Levin details.”

Silent Places: A Tribute to Edward Hopper. The artist referenced in works of fiction, including selections from my own work and that of ISOIS contributor Michael Connelly. (This was my introduction to Gail Levin.)

The Poetry of Solitude: A Tribute to Edward Hopper. As above, with poetry instead of prose; poets include John Updike, Lawrence Raab, Stephen Dunn, John Hollander, Joyce Carol Oates, Edward Hirsch, Grace Schulman, and Sue Standing, among others.

And, of course, lest I forget, here’s In Sunlight or in Shadow—where you can read the rest of Gail’s account of the preacher and his collection.