As many of you may know, just about everything I’ve written, in a lifetime in which I’ve written far too much, is now once again available, much of it through the miracle of ebooks and print-on-demand paperbacks. The passing years have seen Ego and Avarice gain in influence, perhaps at the expense of Self-Respect. In 2020, Terry Zobeck brought out A Trawl Among the Shelves, his exhaustive bibliography of my work—and just about every item he lists is, for better or for worse, readily obtainable.

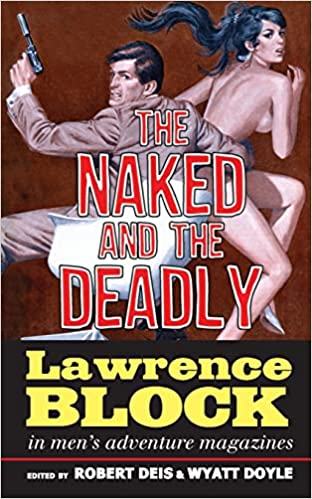

That was not true of a batch of articles I’d written at the very beginning of my career for the men’s adventure magazines. But then along came Robert Deis and Wyatt Doyle, whose particular enthusiasm is those hairy-chested publications of yesteryear. What, they wondered, would I say to a handsome volume collecting all my contributions to that magazine genre, including not only the nonfiction pieces written to order but the various short stories and book excerpts that one or another of the magazines had reprinted.

That was not true of a batch of articles I’d written at the very beginning of my career for the men’s adventure magazines. But then along came Robert Deis and Wyatt Doyle, whose particular enthusiasm is those hairy-chested publications of yesteryear. What, they wondered, would I say to a handsome volume collecting all my contributions to that magazine genre, including not only the nonfiction pieces written to order but the various short stories and book excerpts that one or another of the magazines had reprinted.

What would I say? Well, the first thing I said was “What’s in it for me?” The next thing I said was “Yeah, sure, I guess so. Why not?”

And would I be so good as to provide an introduction?

Um…yeah, sure, I guess so. Why not?

So here’s the introduction. If you enjoy it, all well and good. If you decide you want to read the book, you can order it easily enough in paperback or hardcover. At their own site, Bob and Wyatt also offer a signed limited edition for a few dollars more…

###

A NAKED AND DEADLY INTRODUCTION

For five bucks a week, I chose Scott Meredith over Henry Luce.

Well, in a manner of speaking. It was the summer of 1957. After spending the month of July on Cape Cod, where I wrote a batch of short stories before hunger prompted me to take a horrible job in a restaurant, I quit and headed back to my parents’ house in Buffalo. I’d bought my first car, a 1953 Buick, in order to drive to the Cape, and I cracked it up en route to Buffalo, where I sold it and got on a train to New York. I found a furnished room on East 19th Street and set about looking for a job.

I had turned 19 in June, and had completed two years at Antioch College. Antioch had (and still has) a work-study program; students spend about half their time on campus and the other half getting real-life experience in jobs in their field. My first co-op job had been a year earlier, at Pines Publications, publishers of the Popular Library paperback line and a great array of magazines. I’d spent three months in the mail room, which gave me practical experience as a clerk and gofer, neither of which much appealed to me as a career choice. But Pines was a publishing company, and I knew I wanted to be a writer, and that wasn’t the worst place to start.

Two months in, the fellow in charge of promotion and publicity told me his assistant was leaving at the end of the month, and wondered if I’d like to take his place. When I admitted I was scheduled to return to college, he assured me I should stick with my plans—and I did, but not without some reluctance. I liked school well enough, but from the jump I was impatient to Get Out There and Do Something.

What I did in August was look for something to do—and, back in Buffalo, my folks tried to lend a helping hand. Ralph Tolleris, a fraternity brother of my dad’s at Cornell, was married to a woman who did something significant at Time-Life, and eventually she and I spoke over the phone. I’d spent a week responding to classified ads, and figured I’d be able to get an office job that would pay me $65 a week. Beebe Tolleris was able to offer me a job as a copy boy at Time Magazine. I’d work 9 to 5, Wednesdays through Sundays, with Monday and Tuesday off, and I’d make $60 a week.

I said I thought I’d keep looking.

Now it wasn’t the five pre-tax dollars a week, not really. It was a deep disinclination to take a job through family connections, because what if I screwed up? What if I got fired? And so on. And yes, a path to success often started as a copy boy at Time, much as careers in the film business began in the mailroom at William Morris, but on the first of November I’d be back on campus in Yellow Springs, Ohio, so what was a menial job at Time going to do for me?

Next thing I knew I’d taken a test and landed a position as an editorial associate at the Scott Meredith Literary Agency. There’s an interesting story that goes with it, but I tell it at length in A Writer Prepares, where you can find it at leisure. I got the job—and yes, the base pay was $65 a week, and if you exceeded your quota you could bring in ten or twenty dollars over that figure.

But that was the least of it. I had fallen into what I have never ceased to believe was the best possible job for anyone with career aspirations in any area of writing or publishing. By the time August had given way to September, as it so often does, I knew I wasn’t going back to Antioch, not in November and very likely not ever. It was a good school and they had a lot to teach me, but I was already in the right place to learn what I really wanted to know.

I was at my desk at 580 Fifth Avenue five days a week, reading the stories of wannabe writers who paid Scott to read their work. They didn’t get Scott, they got me or one of my colleagues, and it was our job to read their stories and tell them why they were unsalable, but that we’d welcome more submissions—each, of course, accompanied by the requisite fee. I’d do that until five o’clock, and then I’d go home and write stories of my own. I’d bring these to the office and give them to Henry Morrison, and he’d read them and send them to one editor or another, and most of the time they’d sell for a cent a word, sometimes a cent and a half, bringing me something like thirty or forty or fifty or sixty dollars—but the money wasn’t the point. I was writing fiction! I was selling it, and it was getting published!

In addition to the stories I wrote of my own initiative, sometimes an editor would call the office with an assignment. He needed 2500 words to fill a hole in an issue that was about to go to press, say, or he had a terrific idea and needed someone to write it up. A shipwreck, or a disaster, or a Very Bad Man—generally something it would never occur to me to write, but more often than not an occasion to which I was prepared to rise.

A fellow named Ted Hecht, at a company called Stanley Publications, was the source of most of these assignments. The Scott Meredith offices were at Fifth Avenue and 47th Street, and the New York Public Library was five short blocks to the south, and I would walk there and consult the card catalog and fill out a slip to request a couple of books, and read enough to go home and write an article. That’s how most of these articles came about.

But not quite all of them. The first one you’ll find is “Queen of the Clipper Ships,” and the byline is Sheldon Lord, the name I used on most of these pieces. But the article itself, I assure you, is one I read for the first time in a pre-publication PDF of this very book. I’d never seen it before, and I certainly never wrote it.

Now I’m unquestionably getting on in years. If I was 19 in 1957, well, you can do the math. And my memory has aged along with the rest of me, and it’s among the component parts thereof that no longer function as well as they once did. There are things I don’t remember all that clearly, and others I recall imperfectly. But in this instance I can say with absolute certainty that “Queen of the Clipper Ships” is not my work. It’s listed in Terry Zobeck’s bibliography of my work, A Trawl Among the Shelves, because anyone encountering it with Sheldon Lord’s byline on it would certainly assume it was mine. I thought as much myself, until I finally took an actual look at

But it’s not.

So who wrote it, only to have Ted Hecht hang someone else’s pen name on it? I’ve no idea, and I suspect anyone who ever might have known has long since spiraled on to another incarnation. You’ll note that it appears in the same issue with another shipwreck story, the General Slocum disaster, and slapping the same byline on both pieces is the sort of thing that can happen when an editor’s in enough of a hurry to get copy to the printer. But never mind. I got $75 for “The Greatest Ship Disaster in American History,” and I can but presume that the actual author of “Queen of the Clipper Ships” got as much for what he wrote, and that it didn’t pain him too much to see the credit go to somebody else.

And now I’m comfortable enough seeing it here in this volume, helping to add a little heft to the book, perhaps making it that much more rewarding an experience for You the Reader. Did I write it? Well, no, but here it is, in my book, still wearing my longstanding pen name. So I think we can safely say it’s mine. And, should anyone reading this be seized by the urge to reprint this stirring tale, my response would be the same as if you expressed similar interest in any of the book’s other contents. I am, after all, a reasonable man. I’ll listen to offers.

Ah yes. I learned a great deal from Scott Meredith…

#

Besides the articles—which, I have to say, would be much easier to write now, in the era of Google and Wikipedia—you’ll find some of my early fiction in this volume. There are in fact three novelettes that feature a New York-based private detective named Ed London.

His origins are complex, and perhaps interesting. I left my job at Scott Meredith after a little less than a year, arranged to return to Antioch in the fall of 1958, and in the interim went home to Buffalo and wrote my first novel. (It’s in print now as Shadows, by Lawrence Block writing as Jill Emerson; it was initially published in 1959 with a different title and pen name.) By the time I was back in Yellow Springs, I’d begun writing erotic novels for Midwood Books as—yes—Sheldon Lord, and one way or another I wrote and drank and smoked my way out of Ohio by the end of that none-too-academic year. I wound up, first in Buffalo and then in New York, making a living by writing novels.

Henry at Scott Meredith was still my agent, and the occasional source of an assignment. One was a TV tie-in novel, a book to be published as a paperback original and capitalizing on a television show, in this case one called Markham and starring Ray Milland. (This was not a novelization, which would consist of turning an existing dramatic script into a prose novel; I was to take the character Ray Milland played and come up with my own story for him.)

By the time I’d finished the book, I wondered if it might be too good to sell to the low-rent house that had commissioned it. I showed it to my friend Don Westlake, who encouraged me to show it to Henry, who sent it to Knox Burger at Gold Medal, who’d already bought my first crime novel. (Mona, later retitled Grifter’s Game.) Knox asked for some fixes, including changing the hero’s name from Roy Markham. I picked Ed London, and made the other changes he wanted, and Gold Medal brought it out as Death Pulls a Doublecross. (And later it became Coward’s Kiss. Plus c’est la même chose, dontcha know.)

But then I owed a book to Belmont, a book starring Roy Markham. So I had to write it, and, well, never mind. I did what I had to do, and by then Ray Milland’s show was canceled anyway, but Belmont published it as Markham and I’ve since republished it as You Could Call It Murder.

So there I was, with a guy named Ed London who could go on to star in a series of Private Eye novels, if only I could write them. And I tried, but it never worked. I don’t know why. What I did manage to write was a novelette, and it sold to Man’s Magazine. That was a decent sale to a decent market, and in the ensuing months I managed two more Ed London novelettes, and they went to the same place. And that was as much as I ever had to say about Ed London—except for all the times I’ve recounted this story, which may well add up to more words (if to no more purpose) than all three novelettes and the novel itself.

#

And what else have we here?

“Just Window Shopping” is an early crime story, and probably one that failed to sell to one of my regular penny-a-word markets; someone evidently dug it out and sent to Man’s, and it landed there. “Great Istanbul Gold Grab” and “Bring On the Girls” are extracts from The Thief Who Couldn’t Sleep and The Scoreless Thai, both novels in my Evan Tanner series. “Erotic Life of the ‘Fly Me’ Stewardesses” is an extract from “Sex and the Stewardess,” one of far too many purportedly factual books I wrote as John Warren Wells.

And there you have it. Naked? Yeah, pretty much. Deadly? You betcha.

And by Lawrence Block?

Well, mostly…

Many thanks for allowing us to reprint your classic stories from men’s adventure magazines, LB. And, thanks for helping us spread the word about it. Cheers!